63% of controllers (you know who you are) still need to automate their AP processes

The problem? 99% of solutions overlook the AP adjacent processes that cause real friction. Think: supplier onboarding, invoice capture, approvals, payments, and reconciliation.

That's why Tipalti built a holistic solution for accounts payable that delivers best-in-class invoice and payment workflows alongside integrated fixes for all your other AP pain points.

One connected solution allows you to spend less time putting out fires and more time moving the business forward.

Learn how to remove manual processes from your workflow with Tipalti's free guide.

Pick Your Poison

Debt is like those Coca-Cola Freestyle machines.

Not only do you get to choose between Coke, Diet Coke, Fanta, etc. You can also add any one of a dozen syrups to create something totally custom.

You might find the perfect blend. Or something undrinkable.

And … the further you stray from the classics, the less you’ll know what you’ve got until you taste it.

Til Debt Do Us Part

Welcome to week three of this five-part series on Capital Structure Design.

In week one, we explored the link between capital and strategy. Last week, we broke down how to quantify your business’s demand for capital.

Now we move to the supply side, starting with debt and then equity.

There is some circularity here. The availability of debt depends on the strength of your equity position, and vice versa. If you’re over-leveraged, equity investors stay away. If your cap table is too complex, lenders may hesitate.

For the next two weeks, we’ll look at them in isolation. We’ll bring it all back together in the final week.

Think Like a Bank

Let’s dive straight into the technicals of debt.

The most important thing for determining the role debt will play in your capital structure is to understand the ‘debt capacity’ your business has. This is the maximum level of debt your business can realistically digest.

Your debt capacity will be limited by certain ‘credit’ type ratios, such as:

A maximum ‘loan to asset value’ (much like the way a mortgage works)

Maximum Leverage Ratio = Net Debt/EBITDA

Minimum Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR) = Cash Flow Available For Debt Service/Total Debt Service Cost

Minimum Interest Cover Ratio = EBITDA/Interest Cost

There are others as well, but these are the most common and most useful for this application. These are the things any lender will look at, but you can figure out roughly where you stand before you even pick the phone up to a bank,

Let’s take an example. Imagine we have three businesses that are identical in every way (same EBITDA, cashflow, asset base & industry) except earnings volatility:

Business 1 has relatively stable EBITDA with a realistic downside risk of 20%

Business 2 has volatile EBITDA with a realistic downside risk of 50%

Business 3 has growing EBITDA and is very stable with no real downside risk

This is an extreme example, but it will help illustrate the point.

The cashflow profile (based on the Unfunded Plan we described last week) might look like this:

Summary of scenarios

We should assume that the business with the most downside risk (all other things equal) would have the most expensive debt. It would also be the most restrictive on debt capacity and terms. It could look something like this:

Summary of lending assumptions

Note: These are example assumptions. You can source actual “bank” assumptions from recent term sheets, lender pitch decks, or by speaking with relationship bankers about current market norms for your sector and credit profile. Make a habit of updating your view on credit outlook every time you speak with a banker or advisor.

Now we can ‘think like a bank’ and figure out (with a bit of back solving), what this might mean for debt capacity:

Debt capacity test

Notes:

*DSCR Cap = (CFADS/DSCR Target) x Annuity Factor

**Interest Coverage Cap = (EBITDA/Min Coverage)/Interest Rate

***Annual Payment = Debt/Annuity Factor

Here, you can see how the different assumptions have limited debt capacity for each of the businesses:

In Business 1, the limit is driven by the debt service coverage ratio

In Business 2, the limit is also the debt service coverage ratio, as well as interest coverage

In Business 3, the cashflow limits are not an issue, but the asset value (available collateral) becomes the limit

Let’s flip the perspective and run each of the four credit ratios, assuming the business borrows its full debt capacity at the terms above. We’ll do this for all three scenarios under both a base case and downside case (sensitized EBITDA):

Now the picture sharpens.

Business 3 can fully exploit its collateral base. Even in a downside case, it maintains ~1.5× DSCR and comfortable interest coverage. Banks would see this as an ‘easy lend.’

Business 2, with volatile earnings, collapses to 0.44× DSCR in a downside scenario. On the same base financials as Business 3, it would struggle to raise even $180m (around $100m less), simply because the cashflow volatility risk is too ugly.

This is the clearest illustration of the real cost of cash flow volatility in debt capacity. And this is only tweaking one ‘capital feature’ (earnings volatility). You can see how these profiles could vary wildly across industries, market cycles, business models, etc.

Debt Capacity Modeling in Practice

For simplicity, the above used one period of “pro-forma” numbers. In reality, you’d run this analysis quarterly or monthly on a rolling 12-month basis in your unfunded model.

Debt capacity will move with your base case, scenarios, and sensitivities. Understanding that trajectory is how you decide when, how, and at what price to raise debt.

Now you can start to map debt capacity against your modeled capital requirement:

The blue line is your Capital Requirements Profile built last week (with different scenario options).

The green line is your modeled debt capacity, (using the technique above) against the assumptions in your unfunded model.

Thinking this way lets you visualize what ‘slices’ of debt might be suitable and when. Each slice has the potential to carry different terms and structure to create an overall debt profile to suit the business. More on that in the ‘stacking debt’ section below

As you evaluate your debt capacity over time, it’s common to see step changes in debt capacity at certain points. Where multiple constraints apply simultaneously (like we saw with business 2 above) when you unlock one constraint, the ceiling can shift suddenly to the next constraint.

Debt Capacity vs Bank Capacity

Total debt capacity is not the same as a bank’s capacity for your business. Each lender will want to operate within its own appetite for your credit and also ensure you are not over-borrowing in total.

This matters most for larger businesses, where club deals or syndicates are required to raise the total amount of debt you need.

Every bank will have its own internal rating for your business. That rating reflects your fundamentals but also their own strategic priorities, industry exposure limits, portfolio mix, debt type preferences, and macro view.

I once had a bank pull out because they were at “full capacity” for our industry. At the time, I took it as a personal failure. In my mind, the CFOs of my competitors had locked in their share of that bank’s lending capacity before I did. But then again … I am unreasonably competitive.

There is a lot more to cover here on the ‘execution’ side of capital structure, which is out of scope for this series, but we will return to it next year.

Types of Debt

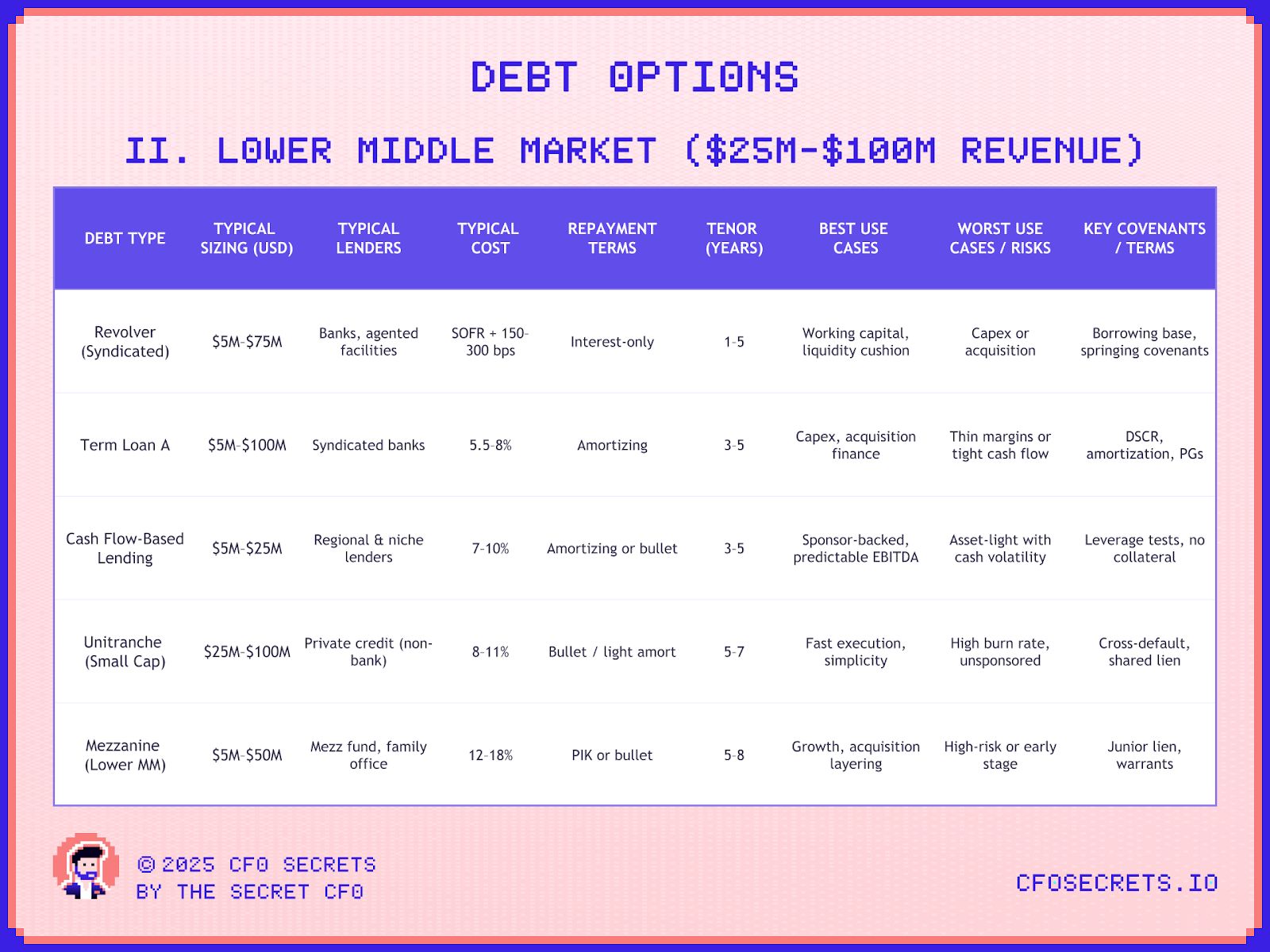

Debt comes in endless varieties (remember the Coke machine?) Far too many to cover in one post. But it’s worth giving you a sense of the main options.

Below is a summary of the most common types of debt and their features, grouped into small business, lower middle market, and corporate, which is the same way most banks organize their coverage teams.

This is just indicative and will vary by industry, geography, etc:

Note - These put the fine in fine print. They’re best downloaded and zoomed in on.

Stacking Debt

Good debt management means stacking facilities to match your capital requirements profile and cash flow. Much like the ‘slices’ I shared above.

The goal is to blend tenor, cost, flexibility, and security to create a structure that fits you exactly. For example, all of these could apply to the same company:

If you have a sticky level of underlying structural debt, a long-term senior facility makes sense. It will cost flexibility, but with a lower cost, and keep the structure simple.

If your working capital is highly seasonal, layer a revolver on top so you can draw when needed and avoid paying for unused capital. You might supplement this with inventory or invoice financing.

If you have a major capex project coming but the timing is uncertain, keep an asset-backed facility (equipment leases) in reserve that you can trigger when you are ready.

And if you one day you are putting together an MBO, you may need a long-term loan or unitranche deal… or even a bond.

Types of Lenders

There certainly aren’t as many types of lenders as flavors of debts, but that doesn’t mean the choice will be easy. One thing you’ll notice is that certain lenders are more suited to different types of debt products.

A commercial bank does not want to own your business. If they find themselves with the misfortune, they will simply sell it to someone who does at pennies on the dollar.

A special sits fund though… well, you can see them foaming at the mouth as you sign the ‘loan’ agreement:

In week one, I shared the story of borrowing emergency funding from a hedge fund. It was expensive (nearly 20%), but that was far from the worst part…

Like a predatory loan shark with an Ivy League MBA, they wrapped us tight: fixed charges on anything with value, floating over receivables, full share pledges, cash sweep clauses, aggressive covenants, and monthly board-level reporting.

I thought it was cautious lending. It wasn’t.

They didn’t want interest. They wanted ownership. This was a classic loan-to-own setup. The debt wasn’t designed to be repaid, it was designed to convert.

We refinanced them out as soon as we could afford it. This was a Trojan horse, not a loan.

Creative Credit

Of course, if you are Meta, you can just invent a new class of credit altogether.

The AI boom, and the “hard asset” data centers that come with it, are forcing big tech to find creative new ways to use debt.

Zuck’s private credit deal ($29bn) was so large it could have been a sovereign debt issuance. But when you have a fortress balance sheet and sit at the center of a generational tech shift, the financing menu options are endless.

Key Lending Terms

While your credit might not be as complicated as Meta’s deal, that doesn’t mean the terms will be easy to navigate.

The whole process is designed to catch you in a bear trap. Even with the best lawyers and investment bankers by your side, you aren’t bulletproof. As I discovered once (but I’ll save that story for another time).

And I find that most CFOs aren’t well-versed in the more technical aspects of lending: security and structures. It’s quite specialist, which is why it deserves an entire series dedicated to it.

While we won’t deep dive into it today, it’s worth at least knowing what the different variables are in a debt deal:

Debt is Discipline

Debt introduces fixed obligations into a world of unpredictable cash flow. That tension creates pressure, and pressure creates discipline.

When your business carries meaningful debt, you can’t coast. You can’t miss earnings. You can’t let the forecast slip. You can’t be late with reporting. Not if you want to keep the lights on.

Private equity knows this. They’ll load a portfolio company with 4 to 5 times EBITDA in debt. It forces focus. There’s no room for drift. It’s life or death, and that urgency can shape a sharper, more accountable business.

There’s a fine line between overloading a business and using debt as a forcing function for maturity. But the effect is real.

Frankly, it’s underused on the IPO ramp. If your balance sheet allows, adding a modest layer of debt in later stages can help instill public-company habits before the plunge. I’m surprised more CFOs don’t take advantage of it.

A Word On Public Debt

We’ve mostly talked about private debt. But once you’re raising $250 million or more, the bond market opens up. This is debt that trades on the open market.

If you’re investment grade (BBB or better), public bonds offer access to large tranches of capital at lower rates. If not, there’s the high-yield bond market, built for sub-investment-grade credits that still need scale.

Functionally, issuing a high-yield bond puts you in public company territory. You’re filing quarterly financials in a format that closely resembles a 10-Q, and distributing them publicly to bondholders and analysts.

You are hosting earnings calls with bondholders and analysts. And in my experience, credit analysts, especially in high yield, tend to be more forensic and less forgiving than equity analysts.

You don’t have a share price, but you do have a bond price. And if that tanks, things can get ugly fast. (Don’t ask me how I know).

The only real difference is that there’s no retail investors watching.

Net Net

Figuring out how much debt your business can take on is just the starting point.

The real edge comes from how you structure it. What slices you use, how they match your cash flows, and which lenders you bring to the table.

The mix matters. A lot. Term loans versus revolvers. Banks versus private credit. Short-term flexibility versus long-term cost. And by understanding what is possible from the debt markets, it can help frame how you think about the ‘supply side’ in the other half of the capital structure (equity).

And that’s where we’ll go next week.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

Find amazing accounting talent in places like the Philippines and Latin America in partnership with OnlyExperts (20% off for CFO Secrets readers)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: TIPALTI ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.