Why does your close still feel manual, even with a close tool?

Because most tools track tasks. They don’t actually do the work.

Ledge gives each close task its own digital staff accountant - an AI agent.

It pulls the data, rebuilds the Excel workpapers, drafts the flux narratives, prepares the journal entries with backup, and hands them back for review, then posts to your ERP once approved.

The team reviews instead of rebuilding.

M********** F****** Cashflow

Imagine two businesses: Business A and Business B.

On the face of the P&L, they are identical twins:

Revenue: $50m

Operating Income: $10m (20% margin)

Free Cash Flow: $5m

But look closer at the expenses.

Business B allocates all of it’s expenditure to Cost of Sales, rent, salaries and admin; keeping the lights on. But Business A includes $15m of breakthrough product development and brand building in its OpEx.

To an investor, Business A is significantly more valuable than Business B.

Why?

Hidden Growth: Business A is aggressively reinvesting for the future, implying stronger future growth prospects than Business B.

Latent Margin: Business A could turn off that $15m "investment" tap tomorrow and instantly reveal a 50% operating margin. Business B is structurally stuck at 20%.

Optionality: Business A’s investments are akin to buying ‘options’ that create potential future organic growth. Placing poker bets on product and sales breakthroughs.

So, how should this affect how you drive cashflow as CFO in your business…? Let’s take a look.

Welcome to Part II of this five-week series on Cashflow Mastery for CFOs.

Last week, we introduced the Cashflow Megaphone. We also explored why cashflow doesn’t really get managed in spreadsheets using the neat accounting buckets we all learned in business school.

Because, well … cash just doesn’t flow like that.

The real movement of cash through a business is far more multidimensional and complex. And if you want to manage it properly, you have to step outside accounting conventions and start thinking from first principles about how individual cashflows behave.

This week, we are going to get technical. We’ll separate cashflow behavior from accounting treatment, so we are ready to get tactical next week. Think of this week as actually reading the instructions before you try to build the IKEA wardrobe.

Specifically, we’re talking about a bespoke definition of cash I developed in the trenches. It’s a metric that cuts through the accounting noise to show you the truth. And more importantly, to help you mentally frame cash decisions properly:

Maintainable Free Cashflow

I’ve written about this before. If you want to refresh your memory, it’s worth revisiting this piece alongside today’s post.

While I’ll briefly recap the basics, I’ll mostly focus on how my thinking has evolved in the two years since I first introduced it.

WTF is Maintainable Free Cashflow?

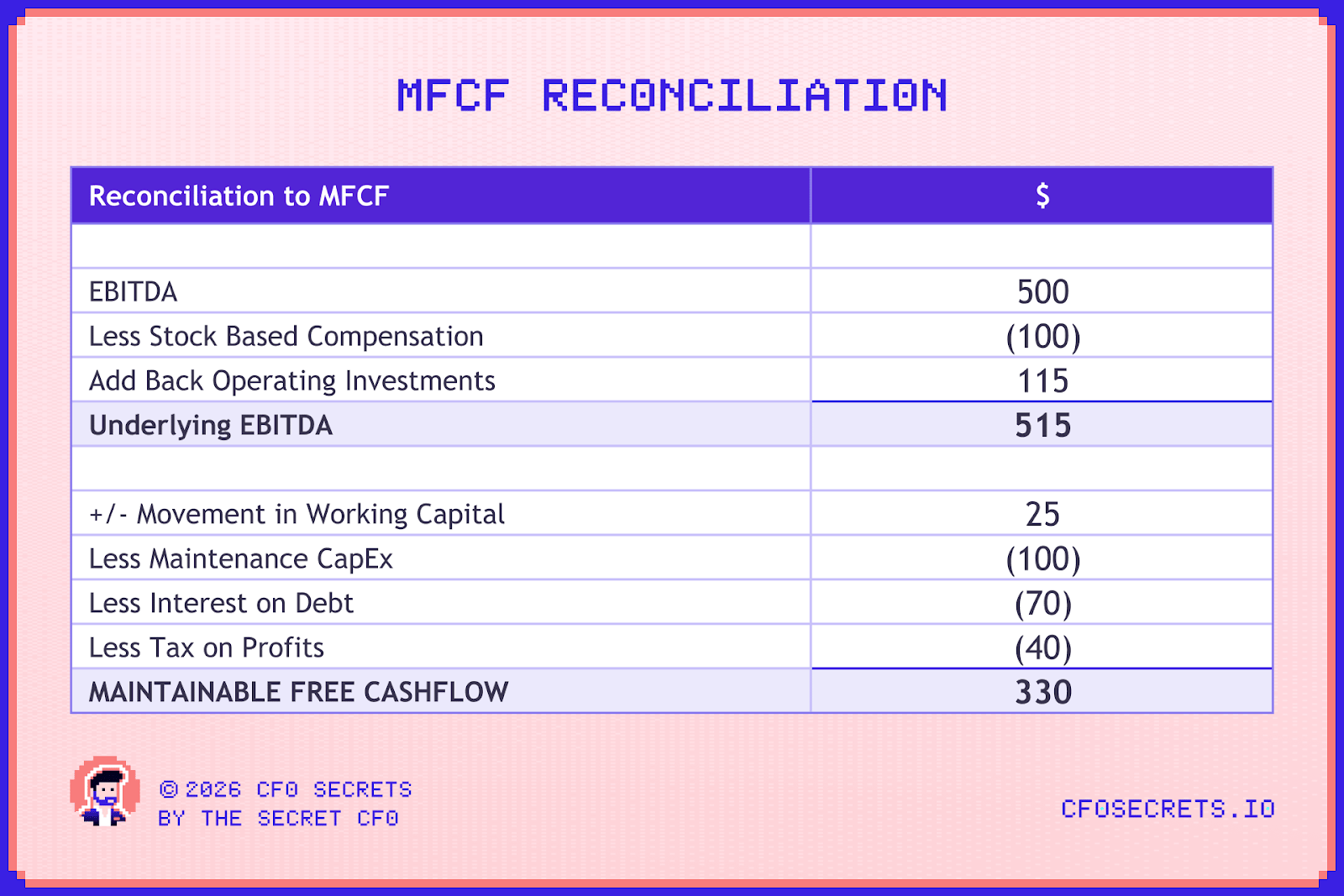

M****** F**** Cashflow for short. Or simply ‘MFCF’ (if you are particularly time poor) is my bespoke, non-GAAP definition of cashflow.

At its simplest, it’s a subtotal inside the cashflow statement that looks past GAAP classifications and focuses on the economic substance of different cash movements.

MFCF separates operating cashflows from non-operating cashflows and capital allocation decisions.

Remember our McDonald’s example from last week?

Operating cashflows are generated in a highly decentralized way, on the frontline facing customers. Employee by employee. Transaction by transaction. Hamburger by hamburger. That requires a very specific type of management system.

Capital allocation decisions, on the other hand, are fundamentally different. And need a totally different management system.

This is a corporate finance problem: how best to deploy capital across competing uses. CapEx. R&D. Debt reduction. Dividends. Buybacks.

Those decisions need to be made centrally. With full context, a clear view of opportunity cost, and with an explicit comparison of alternatives.

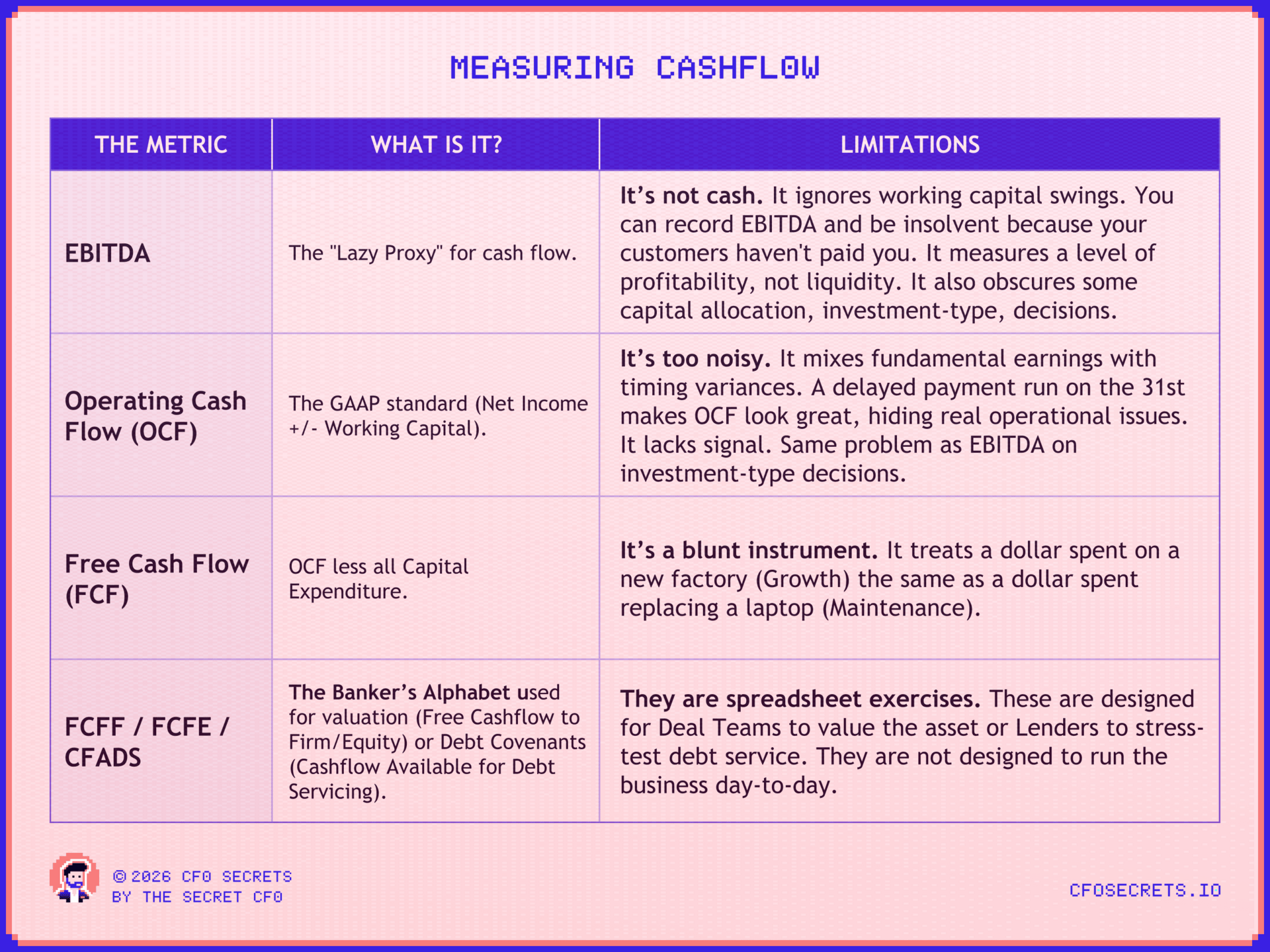

There’s a GAAP for that… surely?

I know what you are thinking. GAAP has been around since the Great Depression. There must be an established metric that makes this easy?

Well… let’s take a look at some of the options for measuring cashflow courtesy of GAAP:

*I know that EBITDA (and most of the others above) are not GAAP-defined metrics. But they are all easily derived from a standard GAAP compliant P&L and Balance Sheet. So, no need to hit reply on this!

Here is the reality: investors are limited to these definitions. From the outside, that is all they can see.

But you, my friend, are the CFO. You are not limited to the captions of the financial statements. You have access to GL-level detail. You own the budget model. You own the management reporting pack.

You have the master key.

It just comes down to how much appetite you have to be intentional about classifying your cashflows by substance, and the discipline to execute against it.

Not all CapEx is equal

Let’s take an example. Some CapEx decisions are "Capital Allocation" bets, others are just the "Cost of Doing Business."

Back to McDonald's. Let’s say they replace their burger ovens on a 5-year cycle. They have a total estate of 10,000 ovens.

Scenario A: They replace 2,000 ovens this year because they are old.

Scenario B: They also buy 2,000 additional ovens for new store openings.

Scenario A is Maintenance CapEx. It is replacing a fully depreciated asset. Without that investment, the capacity of the business reduces. Sales drop. Cashflow shrinks. This is a cost of standing still.

Scenario B is Growth CapEx. It is expanding the capacity of the business, in pursuit of growth and a new horizon for future cashflows. The opportunity cost is different. The decision-making process should be completely different too (ROI analysis, hurdle rates, etc.).

Note: Do not confuse Maintenance CapEx (replacing the asset) with P&L Repairs & Maintenance (fixing the asset). The ‘Maintenance’ in Maintenance CapEx refers to the spend required to maintain the current earnings power of the business.

Despite this vital distinction, conventional accounting simply lumps both scenarios - as the purchase of a total of 4,000 new ovens - and records it as a ‘Fixed Asset Purchase.’

But internally? The economic substance is totally different. You need a process to allocate that spend into the right decision tree, (and a metric to direct that triage).

The concept of Maintenance Capex and Growth Capex has been around for a while. Warren Buffett coined the idea of ‘owner earnings’ 40 years ago, and that included a definition of what we have come to know as Maintenance Capex. In fact, you can read it here. It was when I first read this letter several years ago that I got the inspiration for developing MFCF.

Maintenance CapEx is the average annual amount of capitalized expenditures for plants and equipment, etc. that the business requires to fully maintain its long-term competitive position and its unit volume. (If the business requires additional working capital to maintain its competitive position and unit volume, the increment also should be included)

Introducing ‘Operating Investments’

Now, what about the P&L?

This is where things get messy. GAAP was written for the Industrial Age, an era of factories, inventory, and hard assets. It was not written for the Subscription Economy.

The shape of the P&L has changed. First, software shifted from one-time license models to subscription models. Then, others followed: media, education, delivery services, even healthcare.

Now, much of the economy worships at the altar of recurring revenue. And in doing so, changed how businesses invest.

Recurring revenue is durable. That durability makes it easier to justify huge up-front investments in product development and customer acquisition (CAC) in pursuit of future long-term cash flows. All of which are accounted for in the P&L, but whose cashflow shape looks more like CapEx.

There is no greater evidence of this than the VC boom of the last 20 years. That entire asset class exists to fund P&L losses that are economically more like long term investments.

This is the trap. You spend money now to expand for a multi-year payback.

Conventional accounting (which starts with GAAP) hasn't caught up with how modern businesses are actually run… and won’t anytime soon.

I’m not advocating you capitalize your marketing spend (Please don't do that. And if you do, I’m not visiting you in jail.) But you can capture this nuance when you are modeling, reporting, and allocating capital internally.

And then… channel those decisions into buckets that reflect their economic substance, not just their tax treatment.

So it follows that we should think about Operating Expenses in the same way as Maintenance vs Growth CapEx. Some of those ‘expenses’ are required to keep the business at its current market position. But some are being invested to grow the business. We could think of those as ‘Operating Investments.’

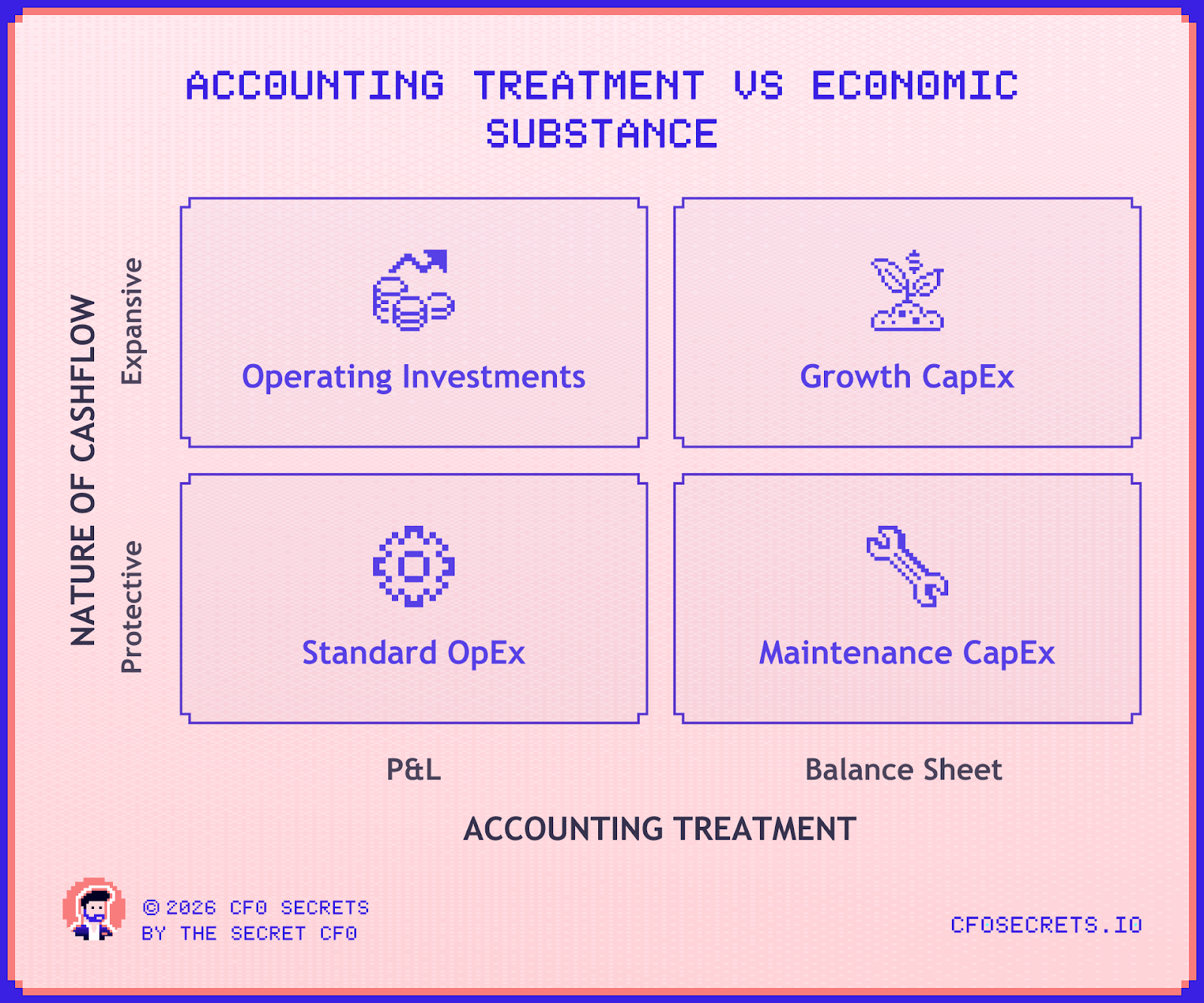

Categorizing Expenditure independent of its accounting treatment

Here is another way of looking at it:

Conventional accounting pushes you to manage in vertical lines. You have an OpEx budget (Vertical Column 1). You have a CapEx budget (Vertical Column 2). You have approval processes for each.

If you want "Cash Mastery," I need you to ignore the columns and look at the rows. I want you to manage horizontally, based on economic substance.

Let’s go deeper…

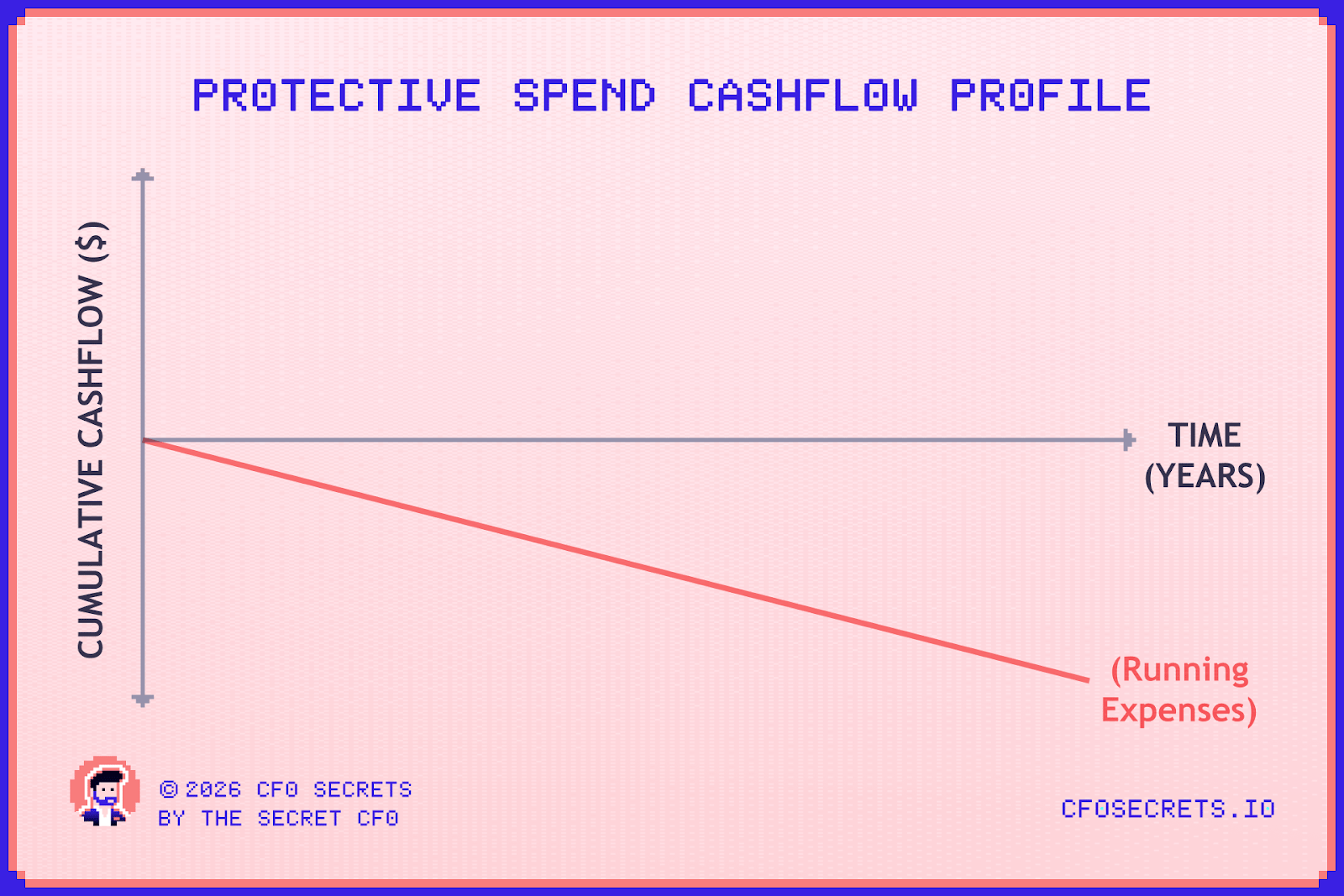

The Bottom Row: The Cost of Standing Still. Look at the bottom half of our grid (Standard OpEx + Maintenance CapEx). Whether it hits the P&L or the Balance Sheet, the cashflow profile of those types of decisions are similar. They (simplistically) look like this

This is the cost of gravity. It includes everything required to fulfill your current order book (COGS, variable costs, fixed overheads, and maintenance capex).

These cashflows are recurring and generally are a function of either time or volume. But crucially, they happen to the business in service of the current revenue and market position.

You pay the supplier for the raw materials (COGS)

You pay the rent and payroll (OpEx)

You replace the broken oven (Maintenance CapEx)

You spend this money to deliver your current volumes and protect your current trajectory.

The Top Row: Now, look at the top row of the 2x2 grid (Operating Investments + Growth CapEx). These are the "Expansive" cashflows.

Their profile is radically different:

These are spent with the objective of delivering a level of future incremental cashflow.

Whether you are building a factory (CapEx), launching a brand campaign (OpEx), or speculating on a new breakthrough product, the physics are similar. You burn cash upfront with the expectation of generating incremental future recurring cashflow.

These are like the Poker Bets we talked about last week. The range of possible outcomes behave more like a probability curve, with varying degrees of certainty. (Represented by the range in the green dotted line.)

CFOs tend to look at these poker bets more like chess moves, which is an exercise in false precision. We will return to how to fix that later in the series…

To manage cashflow effectively, you have to stop looking at the columns (Accounting) and start managing the rows (Economics).

You need a clean dividing line between the 'Cost of Standing Still' (Operational) and your 'Poker Bets' (Capital Allocation).

Conventional accounting blurs that line. Maintainable Free Cashflow (MFCF) makes it explicit.

Why? It comes back to who manages those cashflows and how.

Anything ‘above the MFCF line’ is operational gravity. It is BAU. It belongs to the decentralized organization, where the goal is execution, efficiency, and optimization.

Cashflows ‘below the MFCF line’ (Capital Allocation) are fundamentally different. These are centralized decisions made at the top of the house. They are not about efficiency; they are about opportunity cost, ROI, and placing the right bets.

Let’s Define MFCF…

The definition of MFCF hasn’t changed since my original post, but the presentation has. I’ve refined the language but kept the numbers identical to the original version, so the eagle-eyed among you can tie the two together.

Some Notes:

SBC: Internally, managers often treat stock like Monopoly money because it doesn't hit their cash budget. Fix this. Charge an estimated "cash cost" of SBC to their departmental P&L.

CapEx: Capture the maintenance vs growth classification at source in the CapEx Approval stage to force the spend into the correct bucket.

Operating Investments: For expenses that feel like investments, use payback time and certainty as your razor. Let’s use a couple of examples.

R&D: Take Tesla. A facelift for the 2027 Model-Y would be a maintenance expense. But developing those crazy Optimus robots is definitely a capital allocation.

Marketing: High-velocity spend (PPC) with <3 month payback to protect current volumes would be maintenance spend (MFCF). Long-cycle Brand campaigns? That’s an investment in future asset value and should be treated as a capital allocation.

Interest & Tax: These aren't "choices"; they are the cost of servicing your current capital structure.

Now let’s move onto what happens ‘underneath’ MFCF so we can bring it back to total cashflow, and make sure we’ve caught everything. This is where I’ve changed how I think about the layout:

We start by building up the total available pool of capital starting with generated MFCF. And then the second half of this shows how that capital has been used in the business.

And it starts to build a clearer picture of how and where funds are truly being reinvested vs returned to shareholders vs retained in the business for future deployment.

But… how do you make this real in your business?

Most importantly, don’t take the definitions above as gospel.

Remember, MFCF is a non-GAAP internal measure. There are no SEC police here. There are no benchmarks to hide behind. You don’t even have to agree with my specific examples.

You must be led by the principle, not the rulebook. Define MFCF in a way that captures the economic reality of your specific machine:

The Biotech CFO will need hyper-detailed rules on R&D categorization

The Manufacturing CFO will need precision in their Maintenance Capex definition

The SaaS CFO will need to obsess over SBC treatment and the payback period on growth marketing

Once you define it, you must wire it into the system. You cannot fix this in Excel at month-end. You have to capture the type of expenditure at source. Build the logic into your PO approvals and hiring requisitions so that every dollar is routed to the right bucket before it leaves the building.

This distinction dictates not just where the spend is reported, but the specific approval channel it goes through:

MFCF cashflows - part of your BAU operating cycle

Growth Spend - part of your capital allocation process

And with those two types of cashflows clearly defined, over the rest of the series we will dive much deeper into how to manage each type.

Net-Net

We’ve drawn a clean line between the types of cashflow in the business, based strictly on their economic substance. This is critical, because everything downstream depends on it.

And next week, we head downstream. Specifically, into how you set up the business to maximize MFCF… one hamburger at a time.

This week, I launched The Secret CFO Notebook on Substack, where I share more of my thinking behind the scenes, AND we can interact more directly. This week I shared an example of a legendary earnings call performance from former Apple CFO Luca Maestri - you can read it for free here.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: Ledge ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.