Most startups don’t fail because they didn’t plan

They fail because they planned for just one future… and reality chose another.

When a partnership falls through, a competitor drops prices, or a key hire backs out … the whole plan unravels.

That’s not planning. That’s wishful thinking.

📙 Scenario Planning for Early-Stage Companies is your tactical guide to thinking in tradeoffs — raise or wait, hire or hold, sprint or conserve.

The CFO’s ethical tightrope

Well… here we are. Welcome to the final installment of our 9-week MEGA-series on FP&A. If you’ve missed any part, catch up via the archive here.

Here’s what we’ve covered so far:

FP&A Cycle Overview

Long-Range Planning

Budgeting

Monthly Management Reporting

Monthly Performance Reviews

Forecasting

Bridging Part I

Bridging Part II

This week, we close out with the most sensitive topic of all in FP&A: CFO judgment.

We learned over the last two weeks that:

There are many different ways to calculate variances and adjustments

They can be used in a range of internal and external settings

We explored how variances and bridges are built - and how adjustments can shape the story. And then there are forecasts, which are full of assumptions and judgments.

But when you introduce judgment, you introduce subjectivity. And subjectivity, unmanaged, can slide into narrative distortion.

So this week, we ask:

Where’s the ethical line in CFO judgment call?

When do adjustments help clarity, and when do they cross into spin?

In situations when your job is to ‘sell the story’ of the business, how far should you push it?

And how should a CFO think differently based on who’s receiving the message?

The CFO’s exposure to the risk of narrative drift

The impacts of narrative distortion are subtle but real. And they compound as you move across timeframes and audiences.

Take a simple internal example. If your monthly performance packs consistently highlight “one-off bad news” but ignore equivalent upside surprises, you are creating a distorted view of reality.

That may not seem unethical, since it is internal, but it is still dangerous. You risk creating false confidence, misinformed resource allocation, and complacency.

Now, take that same behavior to the public markets. Cherry-pick the bad one-offs, ignore the good, and you could mislead investors into believing your underlying run rate is stronger than it really is. At that point, you are not just being sloppy. You are at risk of misleading the market, and investors will not go easy on you.

This only gets more complicated when you move beyond the discussion of past performance and into guiding investors on future performance.

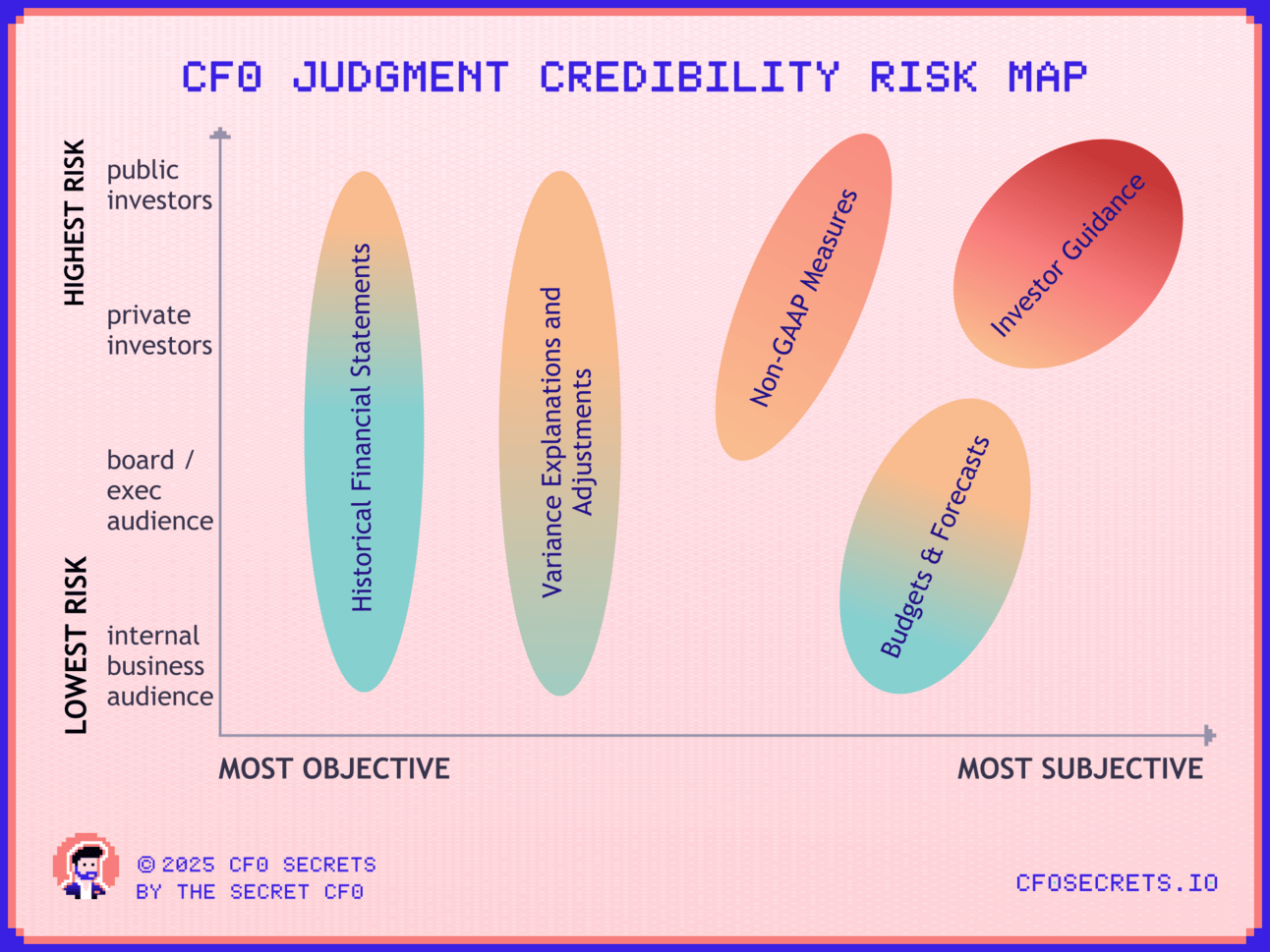

The CFO’s Judgment Credibility Risk Map

Understanding where you are making subjective judgments as a CFO, who those judgments are for, and the associated risk is critical:

Let’s break it down:

Historical Financial Statements: These contain judgment around accruals, reserves, and revenue recognition, but they are governed by hard rules. They allow the least subjectivity.

Variance Explanations and Adjustments: Here, you are interpreting what happened. The analysis is flexible, but your start and end points are fixed. The risk is in classification, not fabrication.

Non-GAAP Metrics: Now you are defining the endpoints on your analysis. Giving you more latitude, more room for bias, and less external verification. Adjusted EBITDA gets a bad rap because it can mean anything you want.

Budgets & Forecasts: These are fully forward-looking. With no real anchor. They carry the most subjectivity and create much more potential for narrative distortion.

Investor Guidance: Again, these are fully forward-looking. Carrying a large amount of subjectivity. But now you are in the glare of external stakeholders. This brings real reputational, legal, and ethical risk.

This framework applies across the full range of CFO communication, from internal reporting to public disclosures. Every point on the map has its own version of risk. But the stakes rise sharply as you move toward the top right corner, where subjectivity is high, and audience exposure is public and consequential.

That is where your judgment is most visible and most vulnerable.

There are three layers to that risk:

What is smart or right for your business

What is ethical

What is legal

We’ll cover the legal line properly another time. It deserves its own post. But here’s the quick version of how to know when you’re blurring the lines between unethical and totally illegal:

You’re presenting forward-looking numbers you know are unlikely

You’re explaining misses with stories you don’t fully believe

But we won’t focus on the legalities of providing forward looking information today.

What we will focus on, is how you operate with integrity in the gray space, between what’s technically allowed and what’s genuinely useful to your business. And how to walk the line when those two things conflict.

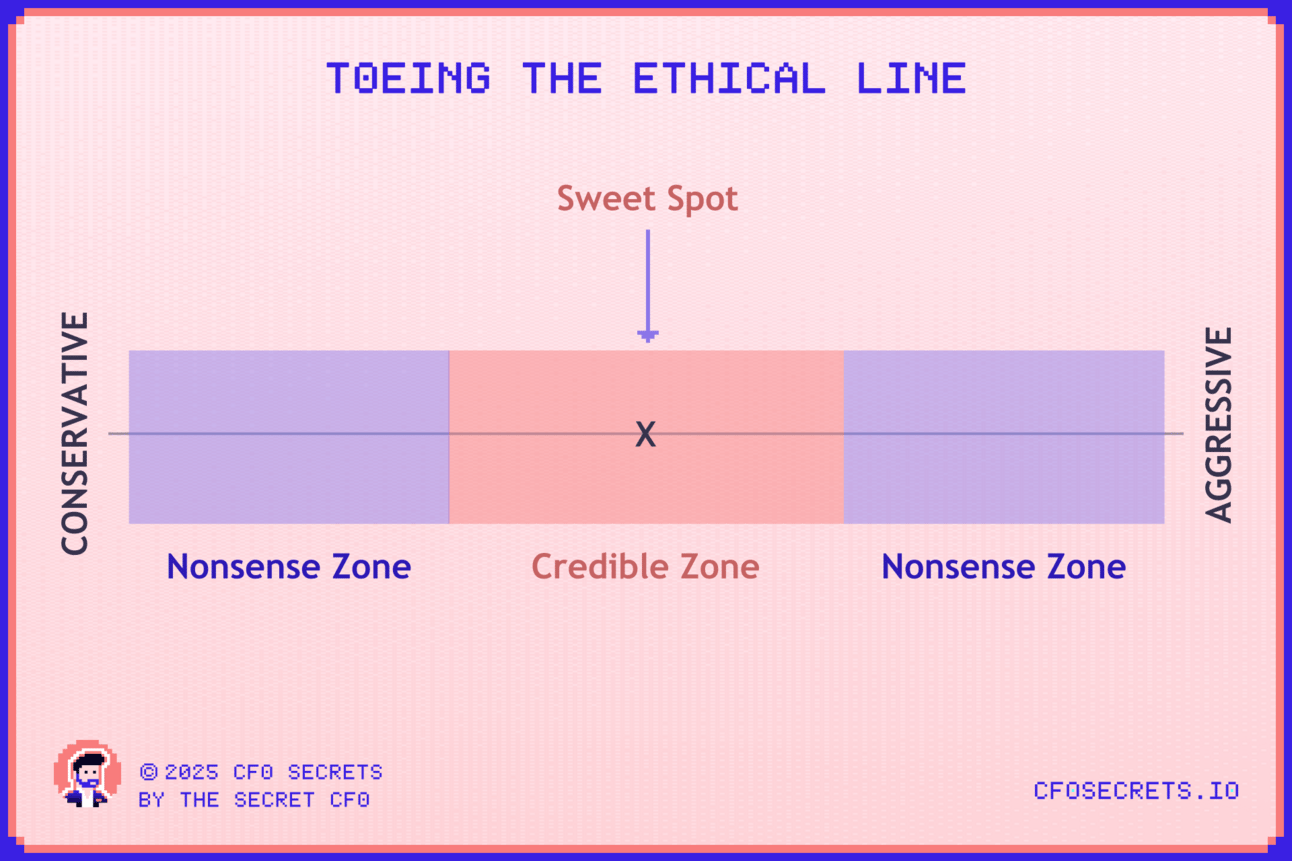

The CFO’s Ethical Tightrope

We can think of any CFO judgment as sitting on a spectrum:

In the center is the sweet spot. Think of this as the “right answer.” The most sensible forecast of EBITDA for the next quarter, the most balanced way to present a bridge, or a fair representation of adjusted performance in a board pack.

To the left of that sweet spot lies the more conservative end of judgment. The further you move in that direction, the more you risk under-stating the performance, quality, or expectations of the business.

To the right, the more aggressive your position becomes. And with it, the risk of overstatement.

The Credible Zone

Of course, in any judgmental area, the sweet spot is a theoretical concept. There’s rarely a single “correct” answer. My view of the expected EBITDA for 2025 might differ from yours.

What matters is this: around the sweet spot, there is a range we can think of as the credible zone. If your judgment, whether it’s an assumption, a metric, a forecast, or a classification, lands within this zone, it would generally be considered credible, even if the actual results turn out differently.

The Nonsense Zone

Outside of the credible zone is the nonsense zone. This is where your judgments are either too conservative or too aggressive to be taken seriously. It is not a place you want to be for plenty of reasons.

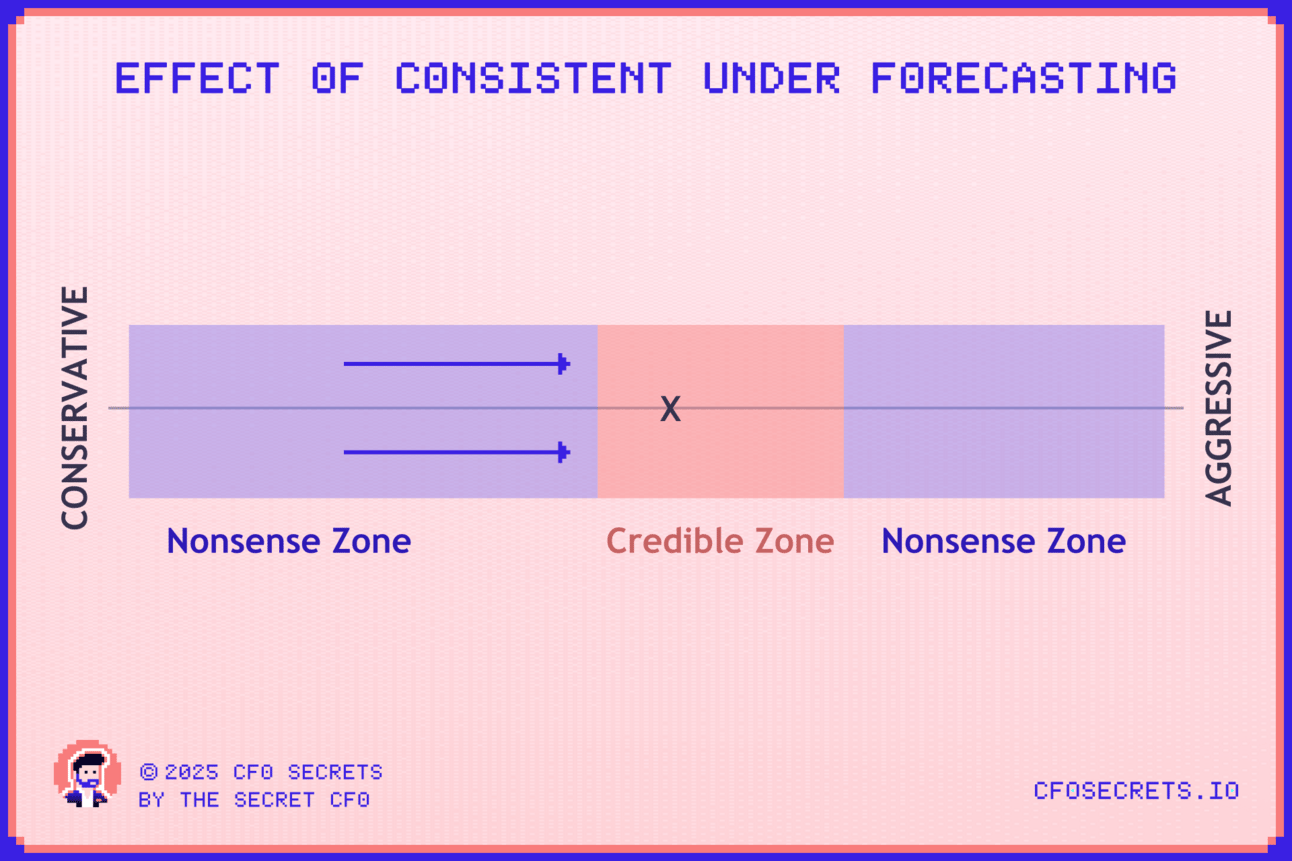

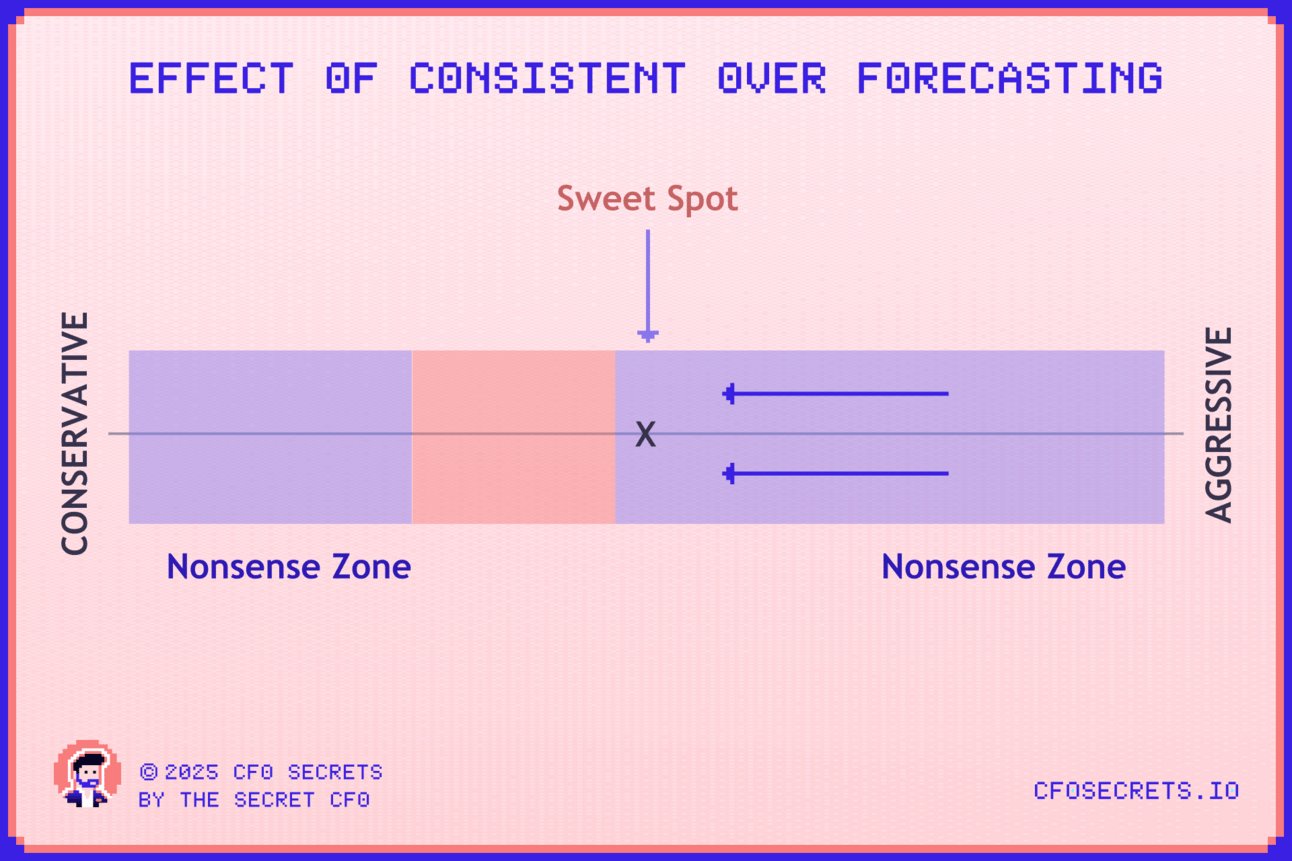

If you consistently provide forecasts that are too conservative - even if they are in the credibility zone - you will eventually erode your own credibility range.

If you tell your board to expect 20 million dollars in sales next month and then deliver 23 million, you might get a pass. Do that a few months in a row, and they will start mentally adjusting your numbers upward. You lose precision. You lose trust:

The same applies in reverse:

If you repeatedly overpromise and miss, your forecasts stop meaning anything. Do this consistently enough, and the credible zone, in the eyes of your stakeholders, can shift inside the sweet spot. Even when you finally fix your forecasting, it may still be hard to get people to take it seriously. That could be fatal. At the very least, you will need to rebuild trust.

Sure, it is better to undercall than overcall. But far better than either is to be accurate. And if you are consistently undercalling, you are not being accurate. You are playing games.

The credible zone in practice

Let’s make this a bit more real. Here are some examples of how judgment shows up in bridges, budgets, and forecasts across that spectrum:

1. EBITDA Bridge Adjustments

Credible: Strip out one-off litigation fees with documentation and no recurrence.

Nonsense: Repeating "one-off" costs every quarter that somehow always smooth the dip. If it’s quarterly, it’s not exceptional. It’s operational.

2. Budget Assumptions

Credible: Base case includes modest volume growth with clear execution levers. Sensitivities are defined and discussed.

Nonsense: Top-line growth assumes magic. No channel detail, no lead gen capacity, and no customer acquisition constraints.

3. Forecasting Working Capital

Credible: Inventory assumptions tied to clear supply chain actions. Receivables forecast based on historical DSO and customer mix.

Nonsense: "We’ll release $10m from working capital" with no mechanism or timing. That’s a hope, not a forecast.

4. Sales Pipeline Forecasting

Credible: Weighted pipeline model with clear stage gating and risk-adjusted conversion rates.

Nonsense: Roll-forward from sales rep wishlists. No aging, no coverage ratios, no kill-rate assumptions.

5. Guidance Ranges

Credible: Clear rationale around how ranges are set vs internal forecasts.

Nonsense: Narrow bands that don’t move even when inputs do. Or bands so broad they look like you don’t have a clue.

Choosing your place on the range

So, how should you apply judgment inside the credible zone?

It’s personal. But here’s how I think about it.

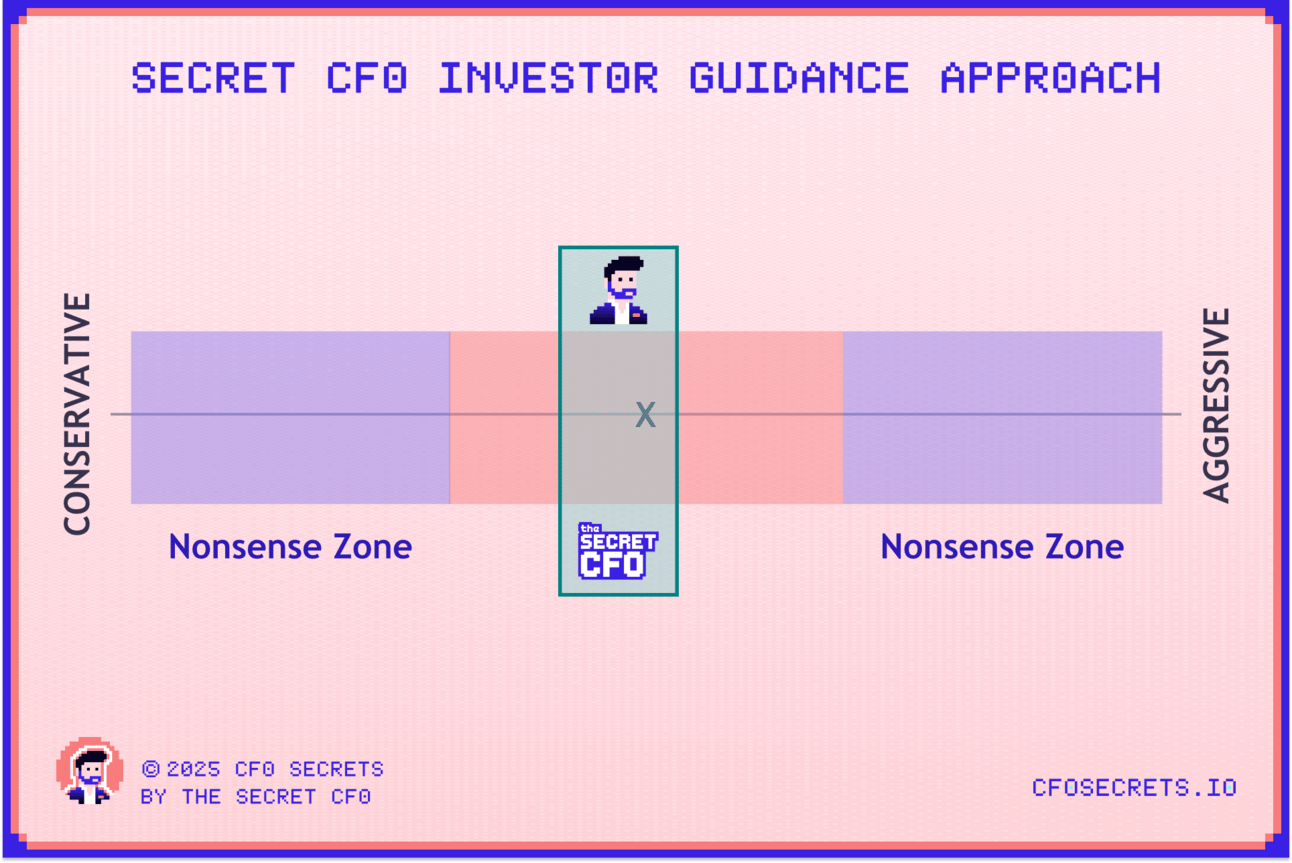

Let’s take a high-stakes example. Issuing investor guidance for next quarter’s EBITDA on an earnings call.

I would always offer a range. One where I have about 95% confidence in hitting the bottom, and 75% confidence in staying below the top.

Put another way: if I guide investors to $50–52 million for next quarter’s EBITDA, that means I’m highly confident I’ll deliver at least $50 million, and I see about a 25% chance of beating $52 million. There’s no science to that split. It’s just how I feel comfortable operating.

Once in five years, I might embarrass myself by missing guidance. But once every year, I’ll give investors a pleasant surprise with a range beat. That feels like a fair trade-off.

This means I am making a deliberate choice to guide slightly to the left of the sweet spot. It’s still credible, but tilted conservative. Visually, it looks like this:

There are other CFOs who guide more aggressively to support the stock price. And others who play it far more defensively.

In my early days in the public markets, I made the mistake of quoting too tight a guidance range for upcoming quarters. Before I really knew the business and how it would respond to macro events. I embarrassed myself once or twice, getting caught out by events beyond the business’s control. But uncertainty is part of the game, and the market expects you to have a grip on it.

Bias Effects

So what stops us from choosing a sensible range inside the credible zone?

Our biases.

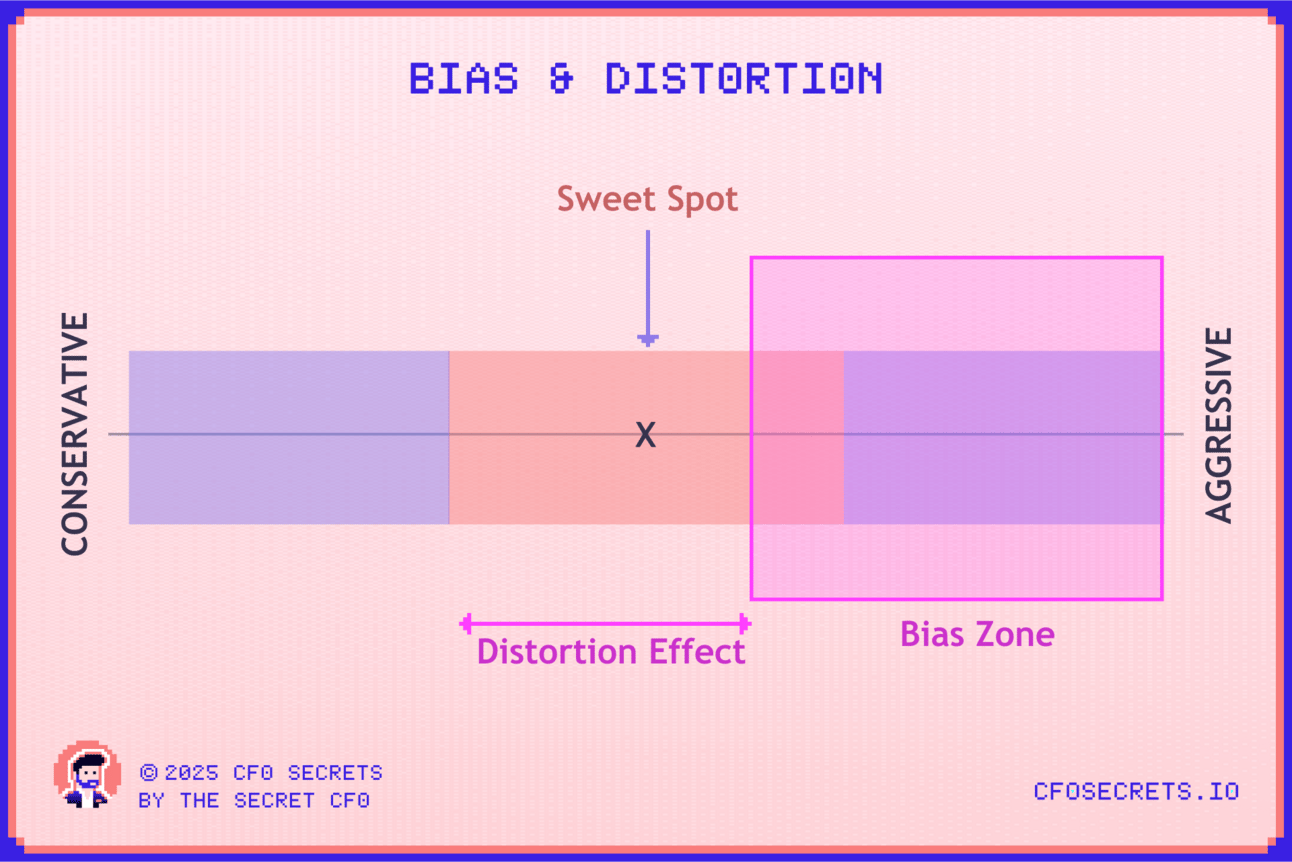

These could be classic psychological biases: confirmation bias, anchoring, overconfidence, pessimism, and so on.

They can show up at the individual level. An overly pessimistic CFO. A CEO who always thinks the best will happen and refuses to build adequate contingencies.

Or they can be institutional, like a company culture that leans habitually conservative or relentlessly optimistic. These biases can be conscious, but just as often they are unconscious. Either way, they create distortion.

Sometimes the issue runs deeper. You might have systems or processes that bake in a forecast error at a structural level.

In my last CFO role, our forecasting process for customer demand consistently overestimated by 1 to 2 percent. We pulled the process apart, looking for the root cause. We never found it. In the end, we applied a flat 1.5 percent write-down as a contingency against the total forecast. Not ideal, since we needed line-level accuracy for supply chain planning, but it was better than knowingly passing along a biased top line.

The point is this: your lens, your window, whatever you want to call it, could be casting a forecast range that either doesn’t include the sweet spot or doesn’t even fall inside the credible zone:

In the short term, you need to adjust for that at the top level. In the long term, you need to rip the process apart until you understand what type of bias is at play and root it out.

I am using the example of investor guidance because it is the highest-stakes scenario. It gives the most acute illustration of how judgment and risk interact. But you could apply the same principles to budgeting, providing a view to the board, or presenting your performance bridge.

My risk appetite would change with those audiences. So my judgment zone would shift slightly to the right, more centered around the sweet spot. Maybe not perfectly symmetrical, but almost.

So what do you do about bias? Build habits that force clarity. Track forecast vs actual religiously, looking for patterns in forecast errors. Back test big assumptions. And when writing explanations, steelman the opposing view. If you’re only presenting the story that makes your case, that’s PR, not FP&A.

I once had a BU CFO who’d over-engineer bridges every time his business unit was under pressure. Always a stack of one-off downsides to explain it away. He wasn’t lying. He probably believed it, but his judgment had drifted. Smart guy… just too close to the story.

Expectation Gap

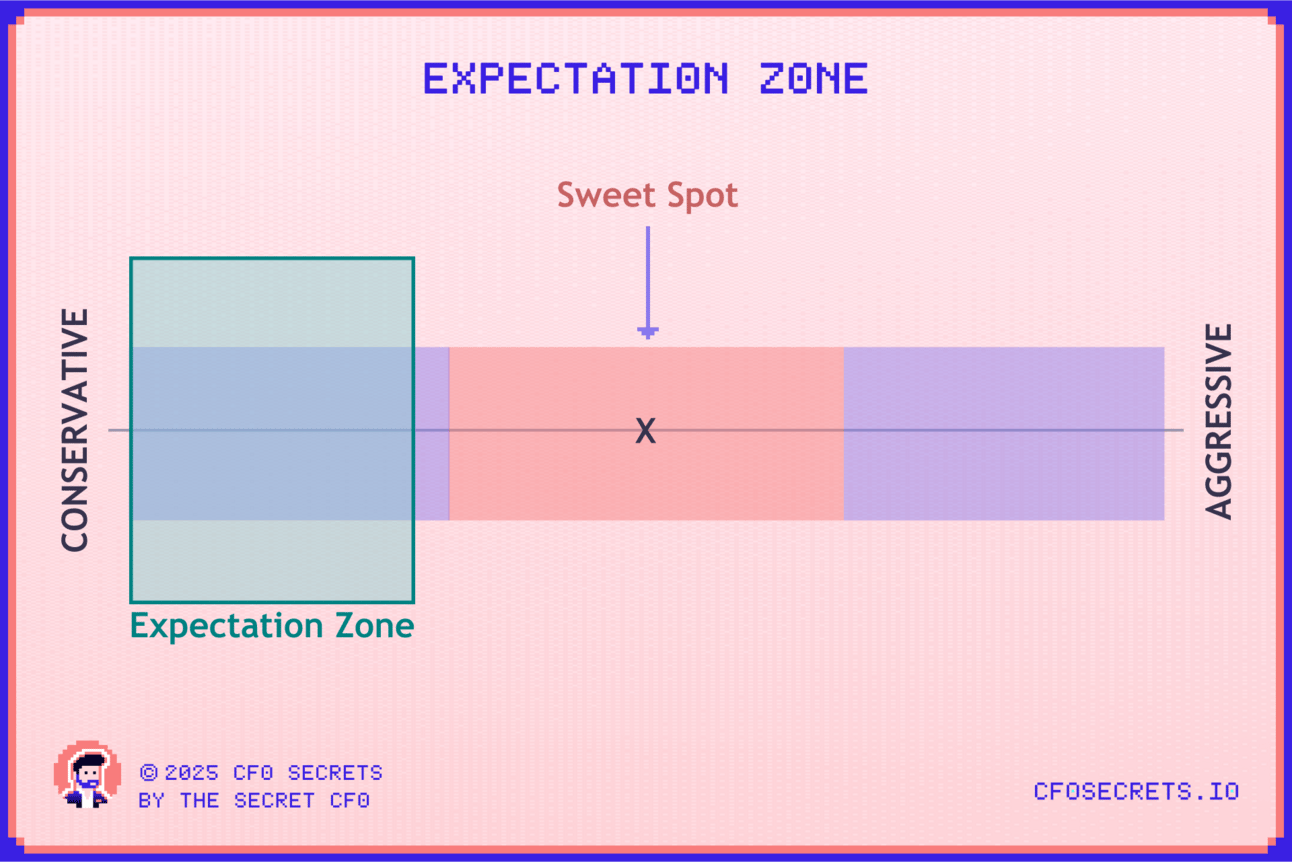

Where things get really tricky in the public markets is when there is a dislocation between investor expectations of future performance and the guidance you provide.

In short, you tell them next quarter will be between X and Y. They don’t believe you. They make their own number up. And now you have a market consensus that sits completely outside your credible range:

This gets particularly hard when institutions have an agenda. A hedge fund pushing a short thesis. An analyst who always overforecasts because they don’t understand the execution risk in your business.

They don’t see what you see. They don’t have visibility into your KPIs and reporting details. So they don’t have the same perspective.

And frankly, part of their job is not to believe you. They are trying to find an edge over the next person. It’s part of the game.

I’ve been in both situations. It’s tough.

If the market doesn’t believe your guidance, you’ve got three moves:

Educate: Engage analysts directly. Walk them through the mechanics. Treat it like onboarding.

Clarify: If consensus is wrong, say so. Use earnings calls or pre-announcements to shift expectations early.

Build Track Record: Hit YOUR numbers. Repeatedly. Nothing fixes disbelief like delivered results.

Just don’t ignore it. The longer you let the gap sit, the more investors will fill it with their own version of the truth.

You can face an expectation gap internally, too. An exec who doesn’t buy into the budget. A board that wants more. But if you’ve walked through the FP&A cycle properly and engaged stakeholders as you go, then they’ve had the opportunity to influence the numbers. They should be bought in. If there are two reasons for that: 1) you are doing a bad job embedding FP&A in the business or 2) you have the wrong exec.

When it pays to be aggressive

Most of the time, the CFO should stay close to the sweet spot, maybe leaning slightly left or right depending on what they're trying to achieve.

But there are exceptions, when you want to be slightly more extreme…

The cleanest example is when you are preparing a business for sale.

If you're building an adjusted EBITDA bridge to present to buyers, your goal is to hit the very top of the credible zone. As aggressive as you can get without tipping into total nonsense. I call this the zone of believable fiction, and wrote about it here.

I’ve sold a lot of businesses over the years, and turning a fair presentation of value into value maximization has become an art form. In a sale, it’s transactional. You are trying to extract every possible dollar. That means showing the full earnings potential of the business, adjusted, normalised, and framed in the best light.

You still need to hold the line on integrity, but you are not the one who has to live with the outcome. It’s the other side’s job to do their diligence and make the counter case.

While a similar dynamic exists in a refinancing or IPO, it’s not quite the same. The pressure to impress is still there - it will drive your WACC for the next five years, or your IPO valuation forever. But now you are also creating expectations you will personally carry. If you stretch too far, you will spend the next four quarters explaining why reality didn’t match the pitch.

That’s the nuance. You want to show the best version of the business. But if it will be your job to report back against that version, you need to be careful.

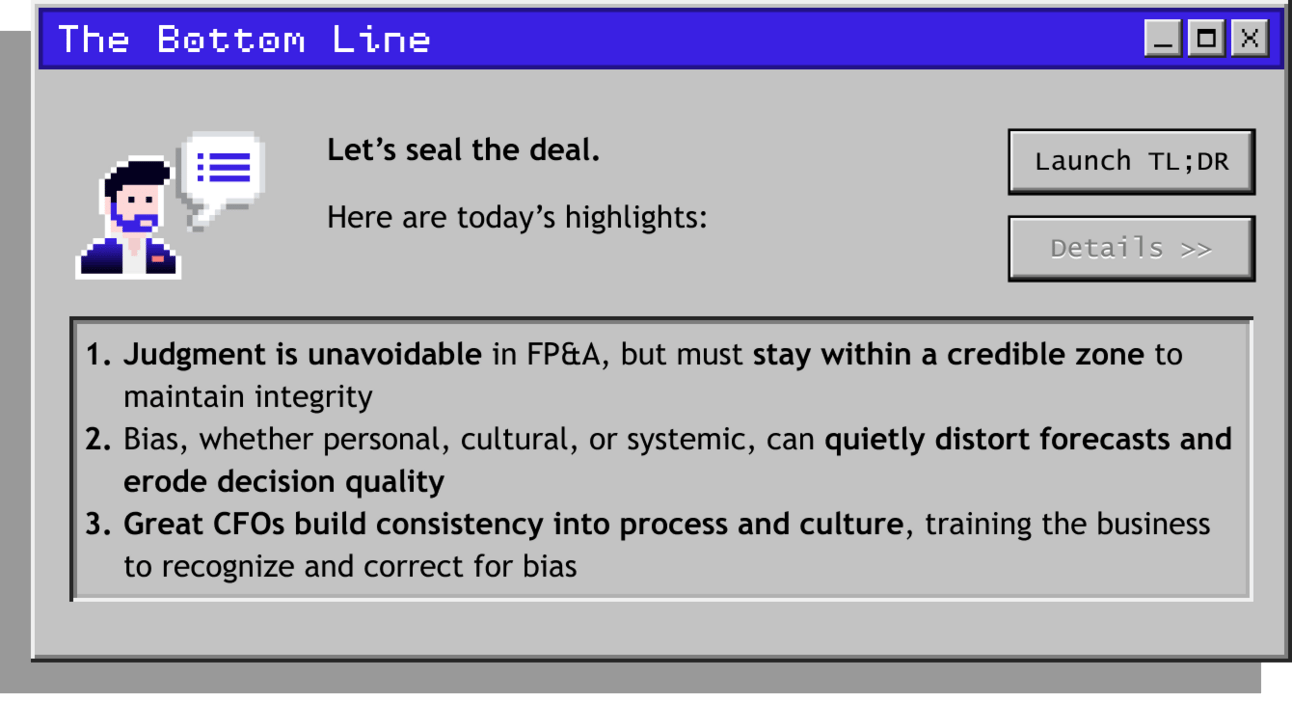

Net-net

Good CFOs have firm and consistent guardrails around how they apply their judgments. They build the confidence of their stakeholders through consistency.

Great CFOs go further. They embed that discipline into the business, first into systems and processes, and eventually into the culture itself.

And with that, we wrap our MEGA-series on breaking down FP&A. I hope it’s been helpful. Keep an eye on your inbox over the next few weeks for a little post-series treat.

Next month, we move on to a new series: tiptoeing through the minefield of corporate politics.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

Find amazing accounting talent in places like the Philippines and Latin America in partnership with OnlyExperts (20% off for CFO Secrets readers)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: RUNWAY ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.