Not making those key hires felt like the right call to protect runway, but how can you be sure?

Burn was getting tight and the model was showing the risk. So you said no to two engineering hires.

But now it’s Q2. Sales missed quota, product’s running behind, and the board’s asking why growth slowed.

What the model didn’t show is that those hires would’ve accelerated a feature tied to $1.2M in pipeline.

Runway fixes that. It shows you both sides of the decision. You drag a hire date, and instantly see what changes across burn, margin, ARR, and payback.

Fool’s errand

“That’s the fourth consecutive month. Is this a joke?”

I’d had enough.

I was four months into my Group CFO role.

This was the fourth monthly performance review I’d attended for this particular business unit.

And this was the fourth time I’d sat through this management team call down their EBIT forecast.

Salami-slicing expectations down four times in four months was a new record for me.

In the first meeting, they announced they were expecting a $4m miss against a budget of $25m. Using a change in Exec to reset their base point.

But in the second meeting, $21m EBIT became $20m.

In the third: $18m

Fourth: $15m

There were only two explanations for this:

They were out of control and had no grip on the business

They were drip feeding bad news to ‘soften the blow’

I’m not sure which was worse.

Either way, I’d lost patience with Stuart, the CFO of the Business Unit.

“Stuart. You have been in this role for 3 years, and you know your business unit well. If there is a problem in the business, your job is to identify it and size it. Once you’ve done that, you need to call the bottom. Quickly. Until you do that, we can’t start building back.”

“Instead, we’ve wasted at least 2 months. And in a performance slide, every week counts. We don’t know each other well, but you need to know, I don’t accept this from my finance teams.”

Then he said the thing that made my mind up. I’m paraphrasing, but the gist was …

“We’ve been running the rolling forecast each month. And we are sharing the answer with you. What more do you want from finance?”

This pushed all my buttons:

Lack of ownership over the output of his team. Unacceptable from a Business Unit CFO.

Lack of ownership over the outcome (reading the news vs making the news)

Blinded by the process. Unwillingness to step back and see what matters behind the numbers.

No understanding of downstream implications. The gap created a cash hole for the Group. And it would blow out guidance with the market. He hadn’t even thought about those points.

Stuart was gone a couple of months later.

But beyond the lackluster performance issues, Stuart’s legacy was a poor culture in the business. This business unit spent too much time re-forecasting and not enough time executing.

On a constant treadmill of replanning bottom-up assumptions and iterating. Not just in finance, but across sales and operations too.

Unforgivable.

Meanwhile, gross margins were being eaten by cost inflation and mix issues. Operational inefficiencies were destroying productivity.

Forecasting is meant to support execution, not compete with it. But in this business, it became the main event. People were spending more time adjusting the plan than delivering it.

A disaster.

Why I hate rolling forecasts (but I might be wrong)

Welcome back to our 9-week MEGA-series on Financial Planning & Analysis. So far, we have covered:

If the first 5 parts were about the ‘P’ in FP&A, the rest of the series is more about the ‘A.’

At the start of this series, I said there were areas where my views had changed since I first wrote about FP&A two years ago. Re-forecasting is one of them.

To start us off, let me explain what I mean by ‘re-forecasting.’

Defining ‘Re-forecasting’

Forecasting is a broad term. But one thing it is not is ‘budgeting’.

One pet peeve of mine is seeing forecasting and budgeting used interchangeably.

Let’s draw a hard line:

Budgeting sets the internal performance contract.

Re-forecasting updates to the latest view of the expected outcome, but doesn’t rewrite the contract.

If you’re rewriting the contract, that is a re-budget, not a re-forecast. And not something you do lightly.

The problem with Re-forecasting

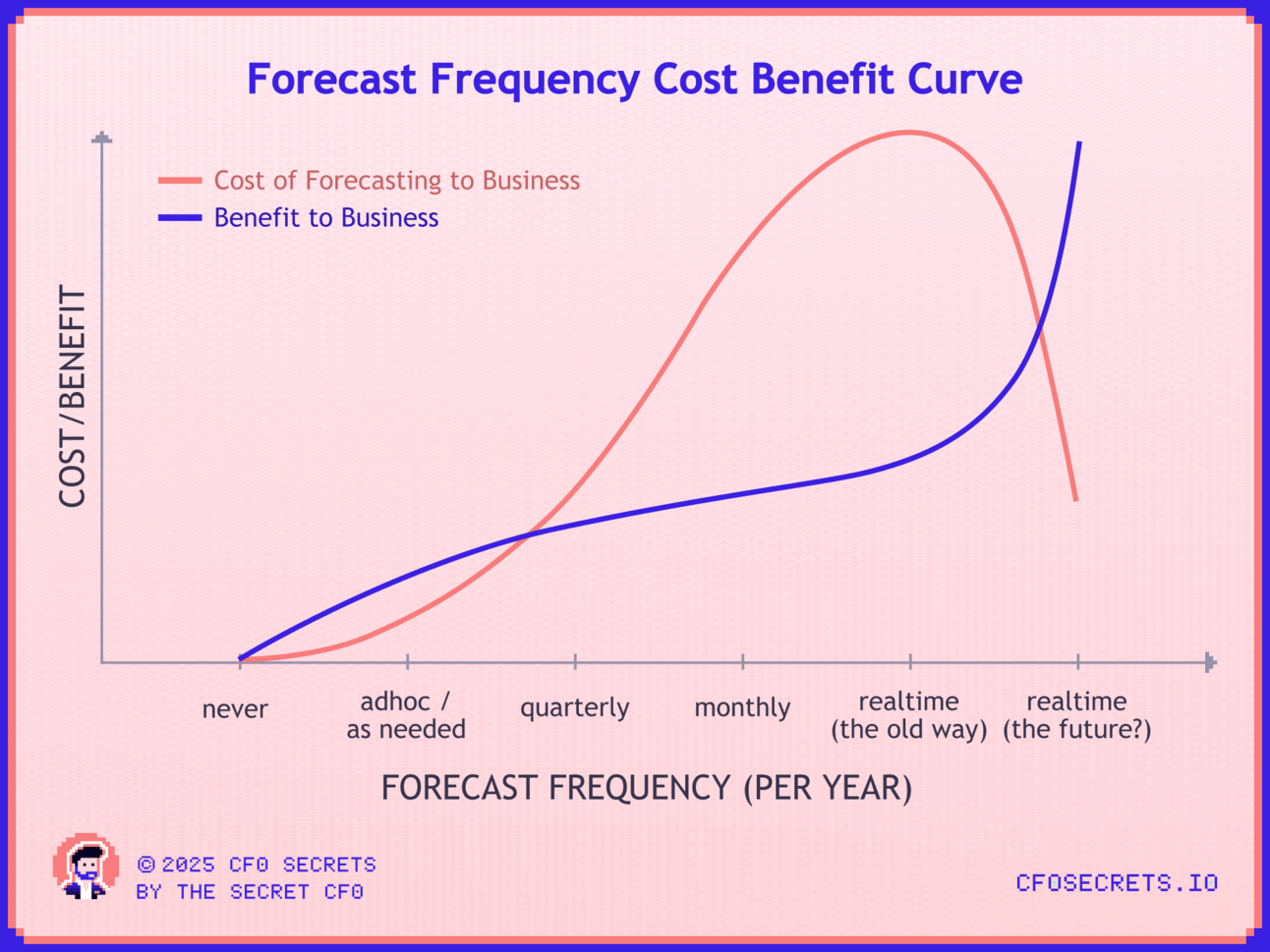

The general narrative around re-forecasting is that more must be better: more frequent and more detailed. The underlying assumption is that finance teams should be chasing the holy grail of real-time re-forecasting with total depth and 360-degree visibility. Sounds good.

I have several problems with this narrative:

It’s mostly been peddled by software companies over the last 10–15 years, most of whom have not (yet) delivered on what they promised.

The hard benefits of more frequent re-forecasting are debatable.

But aside the benefit case, no one… NO ONE… ever talks about the cost of producing a forecast.

Let’s expand on that.

Re-forecasting (by definition) consumes resources speculating about an unknowable future…

The beauty of execution

The best-performing businesses I’ve seen all have one thing in common: they disproportionately focus on execution.

That means obsessing about today.

90% of leadership time and energy goes into delivery. They’re too busy running the business to rebuild forecasts every month.

Their ethos is simple: whatever the future looks like, it’ll be easier if we do a great job today.

Great leaders know when a reset is needed. Until then, they trust the plan and stay the course. They spot trouble early, not because they re-forecast weekly, but because they’re close to the action and pay attention.

They trust their peripheral vision and don’t let the process get in the way of performance.

Who are you re-forecasting for?

Let me be clear:

I don’t hate frequent re-forecasting. There are many environments where it’s essential (especially early-stage businesses). But I do hate lazy, automatic, performative re-forecasting that drains resources.

From my experience, most monthly or quarterly re-forecast cycles are followed robotically, usually because the CFO wanted it. Or because some CFO from 10 years ago thought it was a good idea at the time - and no one ever challenged it since.

Remember, businesses exist to solve problems for customers. Instead of having your sales team spend two hours a month updating pipeline forecasts, that could be two more sales calls.

Instead of asking your ops team to rephase every initiative each month, they could focus on delivering those initiatives.

And instead of tying up support functions in endless headcount and overhead replanning, either take the f*cking overhead out, or let it do what it’s there to do.

Am I making myself clear?!

Any accounting & finance professional should spend 100% of their time doing one of two things:

Help accelerate the things that deliver strategy and create value. Giving the business insights and tools it needs to grow sales, improve margin, tighten working capital, etc

Or …

Stay out of the f*cking way so the people who sell and make things for customers can do their jobs. There are plenty of things finance teams have to do that don’t actively drive shareholder value. That doesn’t mean they aren’t also important… just don’t distract the business in the process.

The opportunity cost of Re-forecasting

Regular re-forecasting can certainly create value or help a business deliver its goals. In many situations, it’s vital.

But there is always a trade-off. There is a cost to each piece of re-forecasting effort. The time, the distraction, the diluted focus. So there has to be a benefit to it to merit that cost. And not just ‘we need the latest information.’ A real one.

So your default should be to kill any re-forecasting process unless you can show it delivers real value.

But don’t take my word for it. This gold from Jerry Seinfeld (gold, Jerry, gold!) is one of my favorite interview quotes ever:

Jerry Seinfeld talking to HBR about his writing process

In this analogy, Jerry and the writer’s room are the business, and McKinsey is the re-forecasting process. And “Are they funny?” is “Will it improve my business performance”?

Start with no re-forecasting, and reason up from there.

Ok, rant over.

Why forecasting is changing

Now, if you have been reading a while, I know what you are thinking: “Secret, you said your views on re-forecasting had evolved. So far, they sound exactly the same as last time.”

Fair. But I had to set the base… now let’s bring some nuance.

First up, what’s changed…

The environment.

Through the 2010s, a good budget was still relevant 6 months later. That world is gone. Or at least has been MIA so far this decade.

COVID, war, energy prices, inflation, interest rates, tariffs… shall I continue? Nearly every year, something has hit that crushed the budget assumptions before the summer was over.

The last five years proved one thing: your budget is one global shock away from irrelevance. So the need to re-budget has become a more fundamental part of the cycle than a black swan.

Next, the tools.

AI and next-gen planning platforms are finally lowering the cost of re-forecasting. Systems that plug straight into operational planning data (sales pipeline, workforce scheduling, supply chain inputs) can now generate financial forecasts as a byproduct of doing the work. That’s a game-changer. Done properly, the incremental cost of keeping a financial forecast current could get close to zero.

And yet…

Most companies still aren’t ready to benefit. The data isn’t reliable. The systems aren’t joined up. And the culture hasn’t moved. The technology is moving faster than the organizations using it.

So yes, re-forecasting is more necessary than it used to be. And it can be less painful. But don’t confuse easy with valuable.

You still have to know what you’re using it for. And what it’s costing you.

The purpose of a forecast

We’ve established that re-forecasting must serve a real purpose. See: “It’s nice to have the latest view” doesn’t cut it.

But not all re-forecasts are the same. There is a clear difference between a quick top down monthly update performed by the FP&A team and a full bottom-up replanning cycle. The cost difference between them is massive (think 10x or 100x).

Let’s simplify it. Every forecast process should serve one (or more) of the following four purposes.

1) Performance Management

The budget is the contract. It sets expectations, drives accountability, and aligns incentives. Re-forecasting to reset targets mid-year can break that system, even in the most robust cultures.

This is where running a ‘risks and opportunities’ tracker pays dividends. It’s simple and action-oriented. And is a lightweight way of keeping track on expected outturn of key metrics. It keeps the focus on what's moving the dial, not rewriting the plan every month.

2) Cashflow and Covenant Visibility

This is non-negotiable. Weekly 13-week cashflow. Rolling 18-month liquidity and bank covenant coverage. Update it more frequently if the situation demands it, but this can be a finance-only process. It doesn’t need to distract the business unless things are REALLY tight.

3) External Communication

Boards and investors want a clear grip on likely outcomes, not a fresh three-statement model every month. Use your existing forecast, then overlay the major known movers using a Risks & Opps lens. Stay focused on ther headline metrics (EBIT, FCF, or EPS). That is enough for most boards and investors.

4) Decision Support

If you're making a strategic move (pricing change, M&A, capex), you can isolate the decision and run the A vs B for your options. This doesn’t need to be tied to a rolling forecast. It can be a separate piece of thinking.

Although if you are in the business of stacking J curve investment decisions where small timing differences could have a large impact, you might need something more connected and dynamic. But that should be a conscious decision, not a default.

Who owns the forecast?

How you govern the forecast and who owns the inputs and outputs is critical. If it’s a full ‘bottom-up’ style process, then the same principles as the budget apply.

But if it’s light touch/top down, then you want a small number of people in FP&A and the exec overseeing the assumptions. The fewer the people who can be involved, the better, without compromising the purpose of your forecast, of course.

Bringing it together

So the question is, how do you bring this together into a cycle that makes sense?

Here are a few things you can think about when designing your forecast process:

Purpose: Who is the forecast for? Is it to drive performance? Or is it for a corporate purpose?

Frequency: Real time, monthly, quarterly, twice yearly, once yearly, ad hoc

Routine approach: For a frequent process, a routine approach is essential. It can be a bit more improvised if less regular.

Triggered by a specific business event: M&A, refinancing, equity raise.

Static or Rolling: Linked to frequency. Is there a meaningful break between forecast windows?

Timing: Where does it sit best in the cycle (timing of LRP and Budget will influence this)?

Integrated vs finance only: This is the most important decision. An integrated forecast involves many stakeholders (more bottom-up). A finance-only forecast is a small team finance exercise (more top-down). With an integrated forecast, you get more accuracy (in theory), but have increased the cost of your forecast significantly.

Scope: Full 3 statements, income statement, or key financial metrics only (revenue, EBIT, FCF)?

There are some situations where regular rolling forecasts are critical, not optional.

Particularly where there is an overwhelming constraining issue around funding:

Monitoring forecast debt covenant compliance

Liquidity headroom/runway

Startups raising equity regularly

To bring this all to life, I have set out precisely how I used forecasts and projections in the annual planning cycle in my most recent role.

The Secret CFO Forecasting Cycle

1) Performance Management (involves business units)

Strong budget = reference for the year

Risk & Opportunities (+ supporting analysis behind each)

By quarter & full financial year

By business unit

EBIT & cash flow

Typically, 1 or 2 reforecasts per year. Just a 6 + 6 in a stable year, and maybe a 4+8 and 8+4 in a more volatile macro.

2) Corporate Purposes: Involves a small number of people in the corporate team who know the business well

13-week cash flow rolling weekly cash forecast (treasury)

Rolling 18-month covenant and liquidity forecast (FP&A)

Ad-hoc re-forecast ahead of major corporate activity, M&A, refinance, new equity

Guidance model for investor relations

For your business, it might be more efficient to just run a regular full 3-statement rolling forecast process. Just make sure you are choosing that because it’s more efficient for the business, rather than more convenient for finance.

The Future

This is where I take the other side of the argument.

I mentioned earlier that improved technology is reducing the cost of forecasting and narrowing the gap between operational planning and financial forecasts.

A few years ago, I dismissed the idea of real time forecasting outright. But that has changed. Thanks to AI, and a new generation of FP&A startups, realtime forecasting that is actually useful and not prohibitively expensive now finally seems to be an option.

So here’s how I’m now thinking about forecast frequency (the curve for your business might be different):

Note: the definition of forecast here is a bottom-up approach requiring high levels of engagement outside finance (explaining the cost curve).

The last generation of FP&A tools promised us the profile on the far right of this chart. I’m not aware of any businesses where this actually played out. Those who tried ended up with the ‘old way,’ and many in practice gave up and settled for something that was nowhere near real time at great cost.

For me, that was an ad hoc 1-2 times per year. For others, it may be quarterly or even monthly.

But this new generation of FP&A tools powered by a breakthrough in AI capability brings data, operational planning, and financial forecasting together. Reducing cost and increasing relevance of live scenario planning. It’s an exciting time to be a finance nerd.

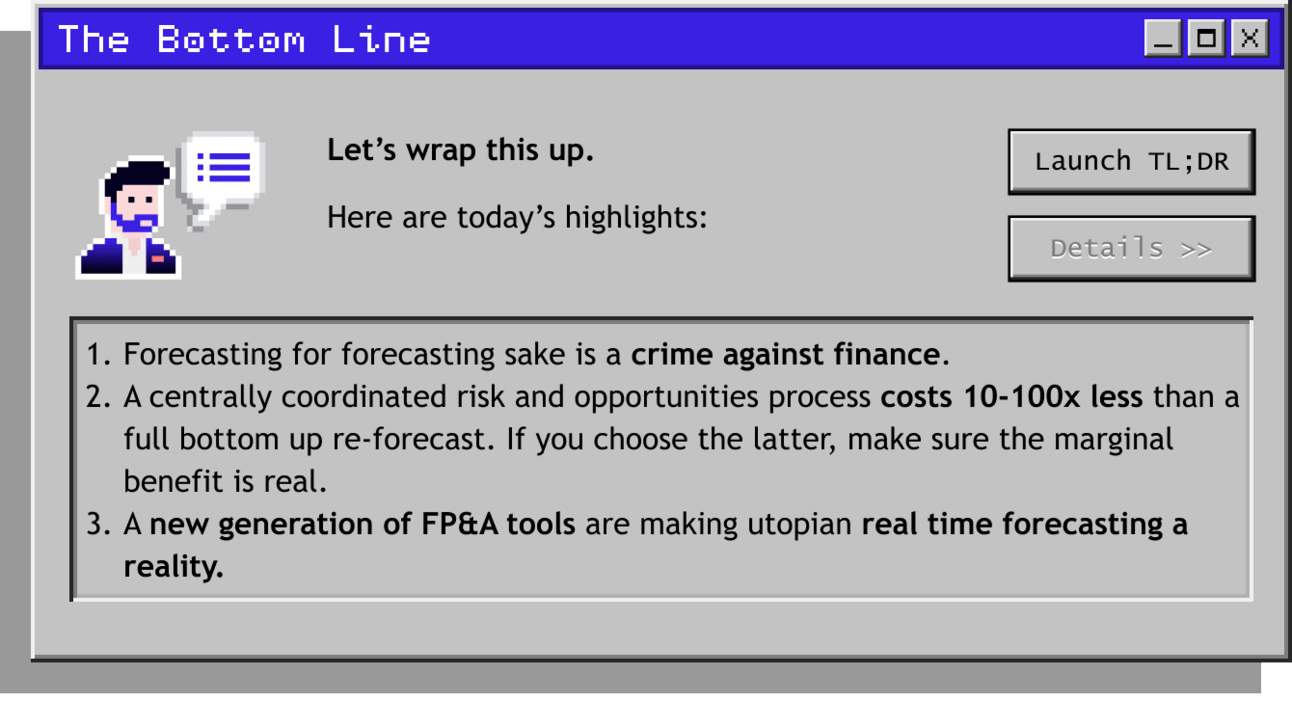

Net-net

My aim here is to challenge you to think from first principles about your forecast, not give you my forecast approach to copy.

Not every business needs the same rhythm. If you’re a startup or turnaround burning cash, your survival might depend on full monthly regular re-forecasting. If you're in a stable, margin-heavy business, twice a year might be plenty. PE-backed? You’re forecasting for credibility as much as control.

Don’t borrow someone else’s cadence, build the one that matches your risk, complexity, and speed. But also understand that technology is changing what’s possible quickly.

Next week, we’ll break down performance bridges - the piece in this series I am most excited about!

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: RUNWAY ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.