Still applying cash manually?

If your team is decoding “inv123-8” memos, hunting down remittances in emails and PDFs, switching between currencies, and reconciling across entities by hand… then you're wasting time, risking burnout, and leaving cash unapplied longer than it should be.

Ledge automates the entire cash application process, extracting remittance from any source, matching payments intelligently, and posting journal entries directly to your ERP with full context.

Watch the 5-minute demo. See how Ledge fixes cash application for good.

Inside the war room

It’s fall of 1982, and Chicago is frozen with fear.

Seven people had died within days after taking Extra-Strength Tylenol capsules that had been spiked with cyanide. A 12-year-old girl, a young flight attendant, and three members of the same family. The idea that a trusted painkiller sitting in millions of households all over America could suddenly turn lethal became front-page news. Tylenol, Johnson & Johnson’s flagship brand, went from household staple to suspected killer overnight.

At the time, Tylenol held around 35% of the US painkiller market, outselling the next four brands combined. It generated hundreds of millions in revenue and nearly a fifth of J&J’s profit. Within days, its market share collapsed to single digits. Stores stripped shelves. The stock price cratered. Advertisers pulled campaigns. Everyone assumed Tylenol was finished.

Even though the poisonings happened after Tylenol left J&J’s factories, the company didn’t hide behind that fact. CEO James Burke and his crisis team focused on two questions:

1) How do we protect people?

2) How do we save the product?

In that order.

Instead of waiting for regulators, J&J moved first. They pulled Tylenol capsules from every shelf in Chicago, then went further. Within a week, they announced a nationwide recall of 31 million bottles. Cost: more than $100 million at the time, or roughly $300 million in today’s money.

The FDA and FBI thought a national recall was excessive. Burke ignored them. He leaned on J&J’s Credo, which said the first responsibility was to customers, not shareholders. He understood that if J&J didn’t restore trust, the brand was dead. Doing the right thing for customers would prove to be the right thing for shareholders, too.

What followed became the gold-standard crisis playbook:

Daily press conferences broadcast nationwide

A 1-800 hotline for consumers and health professionals

450,000 telex messages sent to hospitals and doctors

A dedicated line for journalists with daily updates

Burke himself on national TV explaining the situation

No hedging, no blaming the killer, just transparency. J&J also worked side by side with the FDA and FBI, and offered a $100,000 reward for leads.

When it came time to relaunch, J&J unveiled tamper-resistant packaging: glued outer boxes, shrink-wrapped bottle necks, and foil seals. They swapped vulnerable capsules for caplets. In doing so, they changed the medicine industry forever. Tamper-evident packaging became the standard. J&J mailed out 40 million coupons and cut the retail price to win back customers.

It was expensive: a $150m charge to earnings in all. But the public judged them not on what happened, but on how they responded.

Burke doubled down on product quality and the Tylenol brand, laying it bare in his shareholder letter a few months later: “The most tangible evidence of our continuing commitment to the long term is our mounting investment in research and development.”

Within a year, Tylenol had regained 30% market share. Within two years, it was back at number one. In the four decades since, Tylenol has sold more than $50 billion worth of painkillers. That number could easily have been zero if Burke and his team had taken a different approach.

The $150 million they spent in 1982 now looks like a rounding error.

Introduction

Welcome back to the CFO Secrets Playbook series on crisis management for CFOs.

Last week, we set out why you shouldn’t waste a good crisis, and how to make sure you never do.

This week, we are going to get tactical and set out some key principles for CFOs (or any leaders) in a crisis.

A real crisis will test everything, but here are six practical principles for crisis management I’ve found myself coming back to time and again.

Crisis Playbook: 6 Moves That Matter:

Build a war room

Put your big pants on

Drop down 2 levels

Simplify the message

Control PR (if necessary)

Go manual on reporting

Let’s break each one down.

1) The War Room Operating Model

In a crisis, the first move is to establish a war room. Think of it as a parallel organization running alongside business-as-usual, focused solely on containing and resolving the crisis. It does two jobs: concentrates the right resources on the problem, and stops the crisis from bleeding into the rest of the business.

The war room needs a coordinator. Someone who lives and breathes the crisis 24/7 (minus the occasional nap), reporting directly to the CEO. They should be freed from all day-to-day responsibilities until the storm has passed. Their job is to keep the machine running, chase decisions, and make sure nothing falls through the cracks.

This role is tailor-made for a Chief of Staff, an experienced EA, or a sharp project manager. Someone who knows how to cut through the crap, herd cats, and keep plates spinning under pressure.

Here’s a checklist of the essentials when setting up a war room operating model:

Sidenote: this setup is a lot like running an M&A transaction, key refinancing, integration, or any other high-stakes project. The main difference is that in a crisis, the urgency isn’t optional.

2) Put your big pants on

If Burke & Co. in 1982 was the gold standard for leadership accountability in a crisis, you don’t need to look far for the opposite.

Just four years later, in 1986, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor meltdown in the USSR showed what happens when accountability disappears. HBO’s dramatization of the disaster is gripping because of the human cost. But also because of the sheer paralysis at every level of leadership, from the shift supervisor to the highest ranks of government:

You see the same in Titanic. Leadership dithering, denial, and delay. Lives lost because nobody took charge.

I’ve seen it myself, too, thankfully in much lower-stakes situations, but still crises in our world. People who are normally calm lose their heads. Or worse… pretend nothing is wrong.

One of the unspoken duties of leadership is to stand up in those moments. Think clearly. Communicate simply. Bring order to chaos.

Korn Ferry’s Gary Burnison wrote a great piece during COVID that captures this well.

But you don’t need a framework to get the point. It’s just about putting your big pants on. And not one leg at a time either. You'd better get them on, and fast. Remember, the house is burning around you.

Crisis leadership might only be called for once in a blue moon. But that’s part of what you get paid for. It’s baked into that comfortable salary you collect in the good times.

And remember: the leader should be the last one out of the burning building (hopefully with the right pants on). The CEO carries ultimate responsibility, but as CFO, you stand right there with them, showing the same values, the same calm, the same backbone.

3) Drop Down 2 Levels

In a real crisis, execs should expect to operate at least two levels lower than usual. This is not the time for politics, protecting turf, or giving people space to “develop and learn.” If you’ve got the luxury of that space, it’s not a crisis.

That means the CFO will be deep in the numbers, way past the comfort of summary packs. The CEO will be on customer calls. The COO will be walking the floor.

And there are good reasons for this:

Symbolism: It shows the organization you’re in the fight too, not just issuing orders from the corner office.

Speed: You strip out layers and get decisions made faster. No waiting for reports to bubble up.

Texture: You get detail you could never pick up second hand. What information is hard to get, what suppliers are nervous about, what process roadblocks are slowing you down.

Focus. When the top team takes the load, it frees the rest of the org to keep the wheels turning. Better it takes 120% of your time than 10% of 20 different people’s.

For the CFO, what that looks like will depend on whether the crisis is primarily financial. But expect to get your hands dirty. It could mean:

Building a daily crisis dashboard

Reviewing cash forecasts line by line

Triaging payments in real time

Calling supplier CFOs to reassure them

Chasing key customer debts yourself

Sitting in on exec calls with customers or suppliers to steady nerves

Personal calls to critical investors

And that’s just in finance. You may also need to lend your judgment and influence to unfamiliar disciplines to help out an overloaded exec.

I remember during an operational crisis stepping in to own procurement and supply chain workstreams, because that’s where I was needed most. My deputy acted as de facto CFO in the war room in the vacuum I created.

The point is simple: be ready to do whatever matters most. In a crisis, hierarchy collapses. The work finds you.

4) Simplify the message

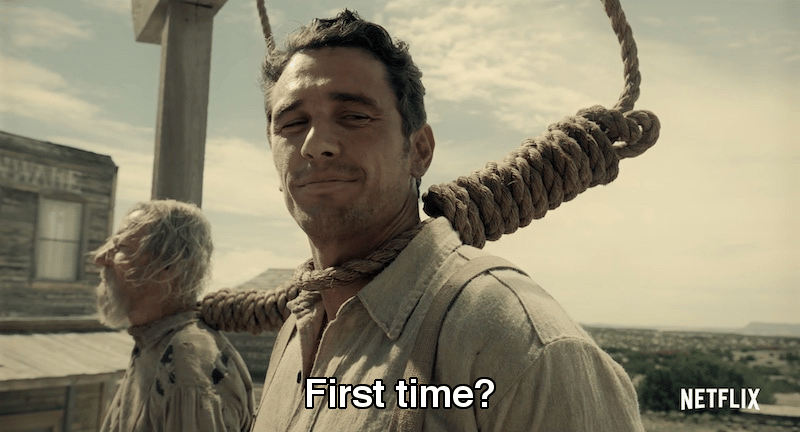

The hardest part of a crisis is keeping it simple. The Tylenol crisis threw a hand grenade of complexity at J&J in 1982: investors panicking, retailers pulling stock, operations frozen, suppliers switching off overnight, employees spooked, police swarming the case, not to mention a murderer still at large. Netflix would have had a field day with this story if it had existed.

James Burke’s brilliance was how he cut through the noise. He defined the crisis response in just two priorities: first, keep the public safe, and second, save the product. Everything else was consequential. By boiling it down to those two simple outcomes (not problems, outcomes), he gave the business a compass it could actually use.

You cannot overstate how valuable that clarity is when people are losing their heads. In a crisis, the to-do list will explode. But if you can reduce it to a handful of desired outcomes, it steadies the war room and reassures every stakeholder that there’s a plan and the right priorities.

The Walter Isaacson biography of Elon Musk tells this story in his businesses, time and again:

Model 3 production hell (2017–2018): Musk obsessed over the “5,000 cars per week” target. It became the single yardstick that determined survival. Everything in Fremont and Gigafactory Nevada was subordinated to that number. He slept on the factory floor until they hit it.

SpaceX rocket reusability: Musk defined success in terms of one number — could they land and reuse a booster? That singular focus cut through the noise of dozens of engineering challenges. It took years, but the clarity of the objective meant everyone knew what mattered.

Twitter (X) cost-cutting: The turnaround plan to one brutal, simple metric: positive cash flow by a fixed date. Everything else was secondary.

5) Control PR (if necessary)

There’s a big difference between a crisis that stays private and one that explodes in public.

If the crisis is contained, your actions are shaped by the facts of the situation and how you handle stakeholders. You don’t control everything, but you can influence almost everything that matters.

The moment a crisis has a PR or public-interest angle, the pace runs away from you. Fast.

Take a simple example: two senior execs caught in an undisclosed relationship. Big issue, yes. But it’s private. The board and leadership team can manage the response on their own terms.

Now imagine that same relationship being blasted onto a jumbotron at a Coldplay gig. Suddenly, it takes on a life of its own before you even know the facts.

In a world of smartphones and social media, the odds of a crisis playing out in public are higher than ever. And when it does, good PR makes all the difference.

One of the best voices on this is Lulu Cheng Meservey. Here’s her rewrite of the dreadful CrowdStrike CEO apology after last year’s outage:

Great crisis PR is a craft. You don’t want to wing it. Pay for a pro when you need one. They have the contacts, they know the journalists, and they can help you ‘control the narrative’.

Note - I planned to include the famous (but vulgar) ‘control the narrative’ scene from Succession here, but Tyler, my editor rightly convinced me it was a bad idea. If you know, you know.

For financial crises, there are excellent PR firms that specialize in working with the business press. I’ve used them before to make sure a complex financial story was clearly understood by markets.

And yes, the first thing any decent PR advisor will tell you: keep the message simple (see point 3). The next thing they will tell you is how insanely expensive they are. But as we learned from Tylenol, the ROI on good PR can be extraordinary.

6) Simple Reporting

I remember in one situation, we had an unexpected major raw material outage. Within 24 hours, it would bring our whole operation to a halt, which would cost millions of dollars per day, every day we were down.

There was a simple analysis we needed to make some quick decisions. Inventory levels, lead times, minimum order quantities, price history,etc for some specific raw materials. I pulled a young superstar analyst into the war room, set them off to get on with it, and figured the urgency was implied (my mistake).

It was taking longer than I needed. I chased them after an hour. Still working. Again, after 2 hours. They needed a little more time. 4 hours. Almost done. Eventually, 5 and a half hours later, they returned with a beautifully formatted piece of analysis, with drop-downs, impact analysis, etc. They told me they’d spent 3 hours setting up automation, so it could be easily refreshed tomorrow.

On another day, it would have been perfect. But it wasn’t what I needed. I needed the raw data in 5 minutes. I’d have taken it scribbled on a sheet of paper. But they’d wanted to impress me and build it sustainably.

This is entirely my fault for not being clear enough on the brief and urgency. I should have recognized that it was their first time in a situation like this, and they’d optimized for the wrong thing.

This is a common failing I see in inexperienced finance people in a crisis situation.

In a crisis, your dashboard doesn’t need to last forever. Write it on a whiteboard. Post bullet points in WhatsApp. Manually key numbers into Excel if that’s fastest.

Don’t waste time optimizing for BAU. Every second counts. Speed to accurate information is the only thing that matters. Not format. Not process.

Net-net

A good crisis response means carving the crisis out of business-as-usual and running it through a separate structure, with its own reporting lines, cadence, and decision rights.

Run properly through a war room, this ensures the crisis gets the resources it needs quickly, without contaminating the day-to-day operation.

The CFO’s role depends on the nature of the crisis and how much it hits cash flow, creditors, and investors. Over the next two weeks, we’ll take each in turn: first, when finance plays a supporting role (next week), and then when the crisis puts finance at the epicenter (the week after).

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

Find amazing accounting talent in places like the Philippines and Latin America in partnership with OnlyExperts (20% off for CFO Secrets readers)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: Ledge ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.