Every other department is launching AI agents. Why is Finance still pulling CSVs?

With Ledge, you can assign a “digital staff accountant” to every task in your close.

AI agents that:

Pull data from NetSuite and other systems

Rebuild Excel workpapers with live formulas

Prepare reconciliations

Draft flux explanations

Propose and post journal entries

Stop wasting talent on the "monthly reset" and give the team the capacity to be strategic partners.

👉 Watch this 5-minute video and see how you can create an AI agent in minutes

Remember the Metaverse?

It belongs on the list of things our kids will (fairly) mock us for in the future. Along with the Cybertruck, AI girlfriends, and worst of all... influencer boxing.

But for a minute the Metaverse was hot sh*t.

In late 2022 , Mark Zuckerberg committed an ongoing $10B+ a year on Reality Labs - a new division building the Metaverse. Zuck said at the time: "This is going to be the successor to the mobile internet."

He was so sure of it, he renamed the whole ass company Meta.

The problem? Reality Labs had no product, no business model, and… no legs:

Wall Street hated it. HATED IT.

The stock lost 25% overnight, vaporizing $200B in market cap.

Why? Because the guidance revealed the sheer scale of the bet.

Investors watched in horror as Meta laid out plans to take 50% of their current free cash flow ($19B in 2022) and punt it into the biggest venture bet ever.

Cue the sharpest U-turn in big tech history.

In 2023, Zuck declared a ‘year of efficiency’: he cut 21,000 jobs - slashing billions in operating costs - which the core business absorbed without blinking. This proved that the P&L had been stuffed to the gills with discretionary operating investments. Risk capital hiding in plain sight as operating costs.

When those vanished, the true power of Meta’s Maintainable Free Cash Flow (MFCF) was exposed. FCF exploded from $19B to $43B in a single year.

Fast forward to today… That $10B Metaverse burn actually looks cute by comparison.

Meta is guiding to $70B of CapEx this year. But this time, it isn't for legless avatars. It is a more permanent bet on AI, locked in concrete, steel, and GPUs.

You can fire people. You can't fire a data center.

Welcome to Part 4 of our 5-part series: Cashflow Mastery 2.0.

In Part 1, we debunked the "standard" way of measuring cashflow and explained why EBITDA is a dangerous proxy for liquidity.

In Part 2, we defined Maintainable Free Cashflow (MFCF) and split the finance world into two distinct systems: Operations (Maintenance) and Growth.

In Part 3, we focused on the engine room - how to maximize MFCF and embed cash discipline into your operation and FP&A cycle.

Today, we cross the line.

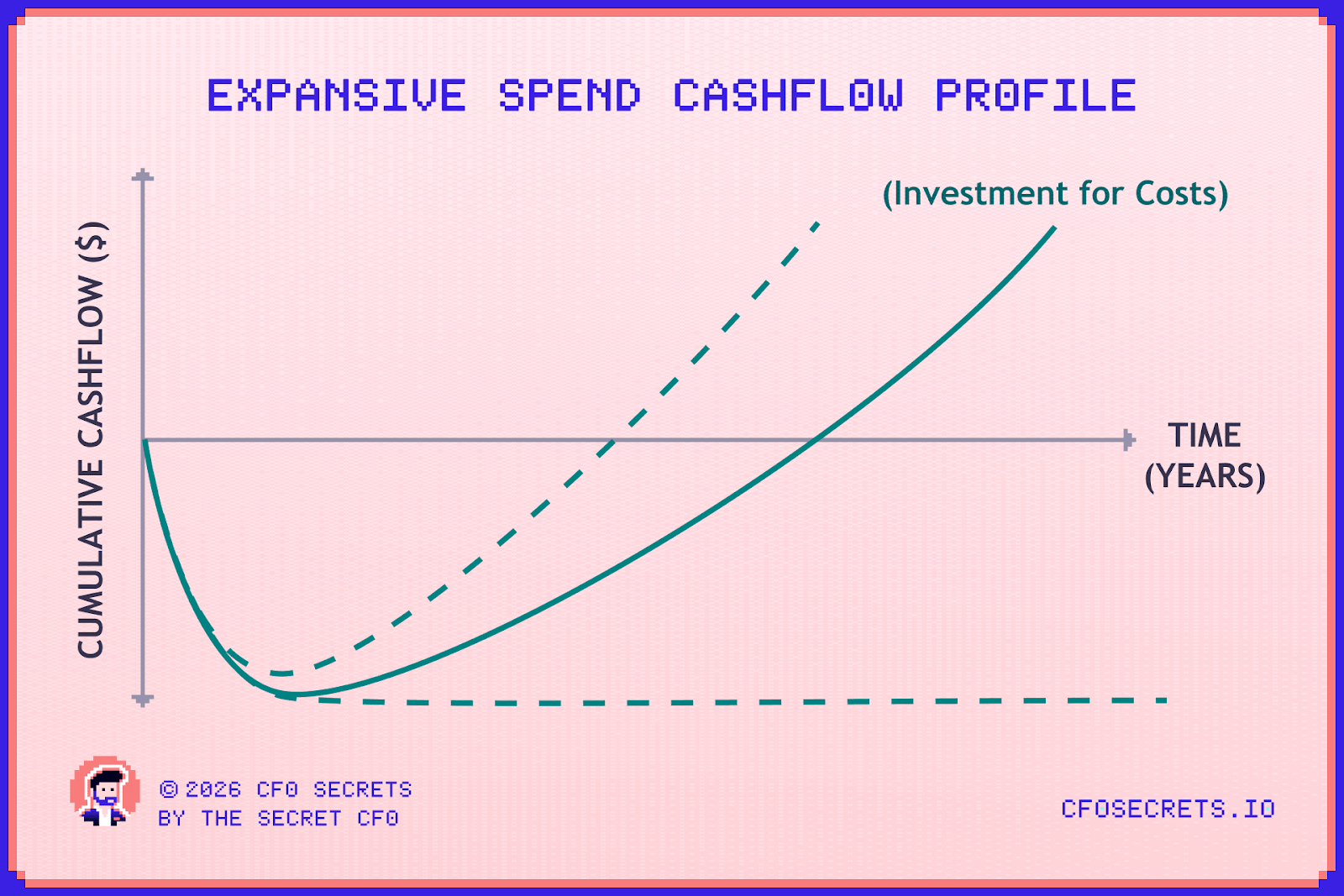

We are leaving the safety of efficiency & optimization, to focus on everything below the MFCF line. These are the 'expansive' cashflows. The strategic bets where you invest hard dollars today for the hope of a recurring benefit tomorrow.

You might remember this chart from Part 2:

Crucial Reminder: We are not getting bogged down in accounting treatment. I don't care if the spend sits in the P&L (like Meta's R&D army) or on the Balance Sheet (like their new data centers).

The only thing that matters to us is the shape of the cashflow itself, not the accounting entry or what some outmoded Financial Accounting Standard says.

The Anatomy of a Bet

To understand capital allocation, we have to look at the DNA of a cashflow.

Every single cash movement - whether it is buying a stapler or a competitor - is defined by five distinct parameters. I call this The Anatomy of a Cashflow:

Direction: In or Out?

Magnitude: How much?

Certainty: How likely is it?

Timing: When does it happen?

Time Value: What is the cost of waiting?

But, that graphic represents just one atomic unit of cash.

In the real world, a major capital allocation decision isn't a single line item. It is an aggregation of (upto) thousands of individual cashflows, each subject to those five variables.

Take a $1B data center build.

That isn't just one "Cash Outflow" for $1B. It is ten thousand separate checks. It is steel, GPUs, labor, concrete, power contracts, and permitting fees.

Each of those components has its own dynamic, its own timing, and its own risk profile. Worse, they are codependent.

If the steel is stuck in a port, the labor is still billing you by the hour

If GPU prices spike due to an AI boom, the magnitude blows out

If the energy permit gets delayed, the entire timing shifts right

And that is just the cash out side - the part you supposedly ‘control’. The cash in side - the return on that investment - is even more volatile.

The Probability Trap

Most Excel models pretend that the future is a single, specific number. But in reality, these J-Curve investments produce a probability distribution. There is a wide range of potential outcomes, ranging from "zero" to "home run."

It is the width of that distribution (the variance) that determines how we should make the decision.

To understand how wide this variance can get, let’s look at two bookend examples:

Bookend A: The “Vending Machine”: At one end of the spectrum consider an established e-commerce brand investing in Meta Ads to grow:

Direction: Highly predictable. You put $1 in, you might not know if you’ll get $2.00 or $3.00 out, but you are unlikely to lose your principal (if executed properly).

Magnitude: Flexible. You can bet $100 or $100,000. The outcome scales linearly with the spend.

Timing: Immediate. This is direct response. The payback can be measured in days.

Certainty: High. The "unknown" is just the precise margin.

Time Value of Money: Irrelevant. When the payback period is days, discount rates don't matter.

Bookend B: The Moonshot: Now, let’s think about the other end of the specturm. Let's look at Apple.

We all know the success stories: the iPod and iPhone bets that created trillions in value. But let's look at the other side of the distribution: Project Titan (The Apple Car).

Apple spent an estimated $10 billion over a decade trying to build an autonomous electric vehicle. In February 2024, they scrapped it. The return on that $10B was $0.

The anatomy of this kind of bet is radically different:

Direction: Binary. There is no guarantee you will win. You can lose and, as Apple proved, you can lose your whole investment.

Magnitude: Unknown. The total addressable market was theoretical. The cost to build it was uncapped.

Timing: The "Valley of Death." Cash flowed out for 10 years with zero return.

Certainty: Effectively zero. You’re betting on non-existent technology and regulation.

Time Value of Money: Critical. The length of the development cycle means there is a real opportunity cost consideration.

BUT… if they’d got it right. It could have been a trillion dollar product, blowing out any other investment they could have made. And the strength of Apple’s balance sheet (and cash generation) means they are probably the only company in the world who could have made that bet.

Just because they missed doesn’t mean the bet was wrong.

The Asymmetry

This is the key insight for the CFO.

In Scenario A (Vending Machines), your upside is capped, but your downside is protected.

In Scenario B (Moonshots), your downside is total (you lose 100% of the capital), but your upside is infinite (you create the iPhone).

The False Math Trap

Of course, these are just the bookends. Most of your decisions won't be as safe as a Facebook ad or as wild as an autonomous car. They will live in the messy middle.

This is what makes capital allocation so tough. It is a ruthless exercise in opportunity cost. Every dollar you bet on growth has to compete not just against other projects, but against the safety of paying down debt, the certainty of building reserves, or the instant gratification of a dividend. All with such different cashflow anatomies.

The temptation is to tame this chaos with False Math.

We are taught to reduce every decision to a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model. We build a 5-year forecast, tweak the WACC by 0.5%, run a few sensitivities, and pretend the output is a fact.

It feels rigorous. It looks professional. But in reality, for the most complex decisions, it’s just false precision.

The Mathefication of Everything

My favorite thinker on this tension is the ad-man and behavioral scientist Rory Sutherland. He describes the danger of reducing business decisions to pure math with a concept called the 'Doorman Fallacy.'

The logic goes like this: If you ask a spreadsheet to analyze a doorman at a luxury hotel, it will define his role as "opening a door." The spreadsheet will immediately suggest replacing him with an automatic sliding door. It is cheaper, faster, and never takes a smoke break.

The math says: Fire the doorman.

But the math misses the value. An automatic door cannot hail you a taxi in the rain. It cannot recognize a returning guest. It cannot signal status and security to the street.

We, as CFOs, are the high priests of the Doorman Fallacy.

We love to "quantify" things.

But the greatest value creation events in history - the iPhone, the Nike brand, the cloud - did not happen because a spreadsheet said they would. They happened in design labs, creative departments, and codebases, often in spite of the finance team.

And the problem is getting worse.

As we get flooded with more data points, the temptation to engage in "false financialization" grows. We have become slaves to the altar of ROI, demanding that every qualitative good be dressed up in a quantitative costume just to get a meeting.

How many times have you sat in a pitch where a CHRO tries to calculate the precise dollar value of "employee engagement"? Or a CTO promises that a new ERP will deliver a specific basis-point improvement in gross margin?

Let’s be honest… most of it is performative nonsense.

Great employee engagement isn't a variable in an ROI formula. It is an outcome in its own right, the soil from which all future business value grows. If you need a spreadsheet to tell you that having a motivated, aligned team is "worth the investment," you shouldn't be in the seat.

But… this doesn't mean we abandon math. It means we must be incredibly careful about how and where we apply that math.

The 4 Types of Capital Bets

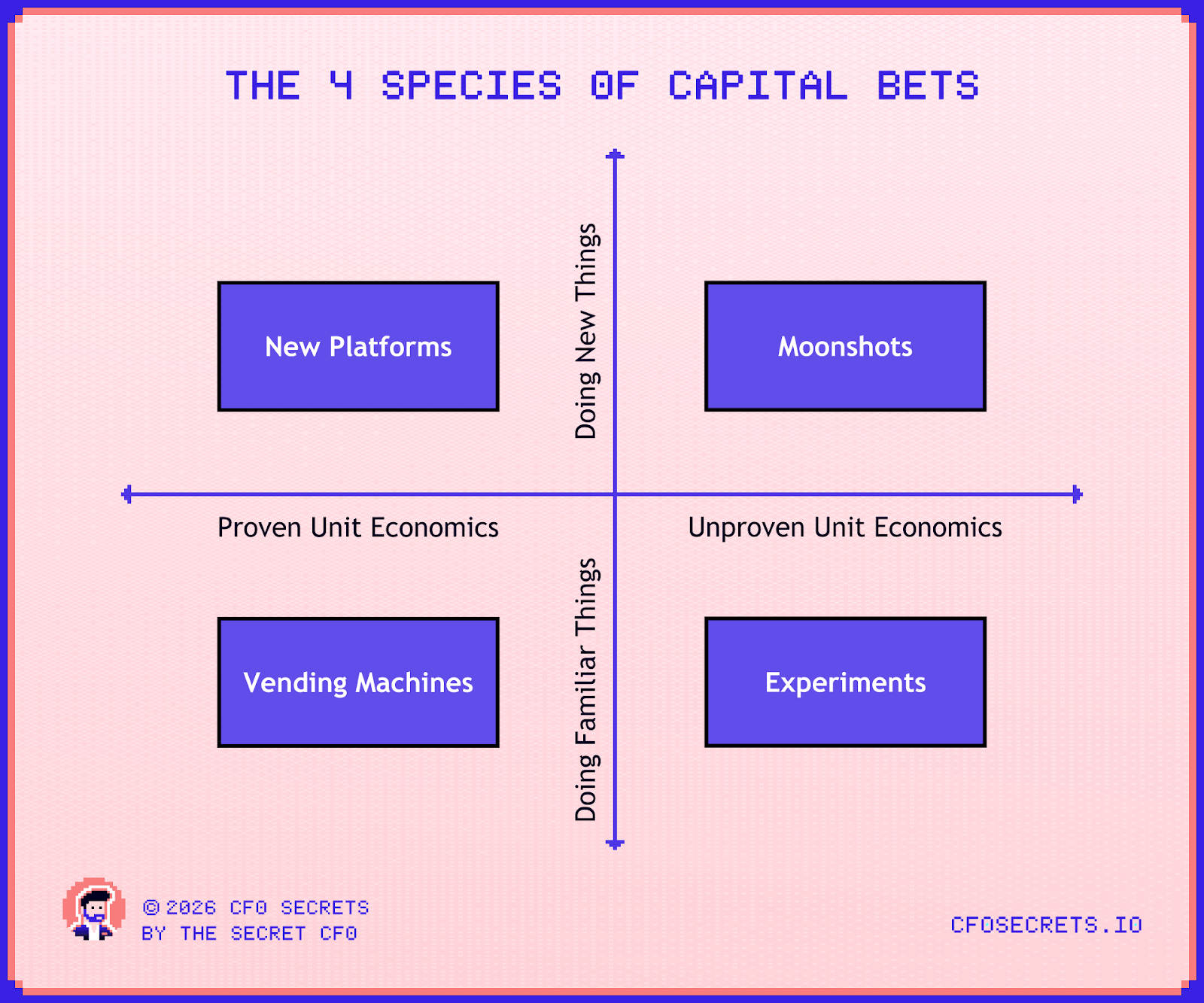

And to figure out just how much math we should apply, we need a way of categorizing our ‘below MFCF’ capital allocation cashflows. And you know I love a 2x2 grid...

We can map every capital decision on two simple axes:

Unit Economics (X-Axis): Is this capital going into Proven or Unproven unit economics?

Familiarity (Y-Axis): Are we buying New Capacity (doing more of the same) or New Capability (doing something new)?

This gives us four distinct species of capital bet:

1. The Vending Machine (Proven Math/New Capacity)

Examples: Performance marketing, growing inventory for bestsellers, hiring sales reps in proven territories.

Features: This is where the math works. High velocity, granular, linear returns where feedback is almost instant.

The Trap: Diminishing Returns. Assuming past returns will last forever or scale infinitely.

Key Metric: Unit Economics (LTV:CAC / ROAS / Contribution Margin).

CFO Mode: The Spreadsheet Guy. This is just math. If the machine is printing money, feed the beast. Your job is to remove budget constraints and fund it, whilst maintaining the guardrails to catch the exact moment efficiency breaks.

2. New Platforms (Proven Math/New Capability)

Examples: New factories, M&A, vertical integration plays, massive distribution centers.

Features: Lumpy, expensive "J-Curve" investments where execution risk outweighs market risk.

The Trap: Gold Plating. Scope creep that adds cost without adding value.

Key Metric: On-Time / On-Budget.

CFO Mode: The Disciplinarian. The plan is proven. The risk is in the execution. Your job is to enforce strict milestones and ensure conformance to the blueprint.

3. The Experiment (Unproven Math/New Capacity)

Examples: New country pilots, pop-up stores, pricing tests, small acqui-hires.

Features: Small, contained bets designed to buy experience and data rather than immediate revenue.

The Trap: The Zombie Project. Keeping a failed test alive because "we just need a little more time."

Key Metric: Time-to-Insight / $-to-Insight.

CFO Mode: The Gatekeeper. Keep bets small, fail fast, and kill anything that doesn't prove the math quickly. Your goal is to build an engine that can run these experiments at speed.

4. The Moonshot (Unproven Math/New Capability)

Examples: Project Titan (Apple Car), Pharma R&D, Foundation AI Models, Business Model pivots.

Features: Binary (0 or 100x), asymmetric bets with long horizons and high cash burn. You are buying options.

The Trap: Balance Sheet Fragility. Betting the farm on a speculative outcome.

Key Metric: Technical Milestones. Ignore ROI and focus on "did the technology work?"

CFO Mode: The VC Investor. Ringfence the capital. Treat it as a separate portfolio. Release funding in tranches only when technical hurdles are cleared.

Constructing a Capital Portfolio

The real art isn't just managing the buckets; it is deciding how to allocate your scarce capital between them.

This is arguably the single most strategic question a CFO faces.

By 2006, the iPod was a Vending Machine generating $7.7 billion in Revenue - nearly 40% of Apple's total sales.

The easy move would have been to reinvest every spare dollar into selling more iPods to maximize the area under that curve, and then flood the results back to shareholders.

Steve Jobs didn't do that. Instead, he took a large share of the cashflow generated by that Vending Machine and ringfenced it for 'Project Purple' - the iPhone.

He took capital from a Proven Vending Machine (The iPod) and bet it on an Unproven Moonshot (The iPhone).

The math looked terrible at the time:

The Vending Machine had an immediate payback and high certainty.

The Moonshot had zero revenue, massive execution risk, and - crucially - threatened to cannibalize the very iPod business that was funding it.

But that single capital allocation decision created $3 Trillion in value, and the rest is history.

The mix you choose between the 4 species is both a strategic question and a math question. The ultimate strategic unit economic challenge.

You can’t just "wing it." You need to set clear rules for each bucket that feed into your Long Range Plan and budgeting cycles, and ultimately into how you price your portfolio and build your business.

Here’s an example of the kind of rules you could build:

The Vending Machine: "Unlimited budget, providing LTV:CAC remains > 3:1 and Payback is < 90 days."

New Platforms: "Must clear a 20% IRR hurdle and be fully funded from existing operating cash flow (no debt)."

The Experiment: "Capped at 20% of Marketing OpEx, with a mandatory 'Kill or Scale' review by project at 90 days."

The Moonshot: "Ringfenced at 1% of revenue, with funding tranches released only upon technical validation. Must be spent."

Ultimately you need to be evaluating these internal investment opportunities against returning funds to shareholders, or strengthening the balance sheet. I wrote about this in 2024’s Capital Allocation & Financial Policy series.

The Meta Lesson: Moonshot vs. Platform How "brave" you can be depends on your strategy, your management quality, and the strength of your balance sheet.

Back to when the market panicked after Zuck announced his plan to pour billions into the Metaverse. It was a pure Moonshot (Unproven Math/New Capability). It was a "YOLO" bet on a digital reality that didn't exist, with no asset backing. If it failed, the money was gone. But it was also easy to reverse; a two-way door.

Compare that to their pivot to AI Infrastructure. The dollar amounts are even larger, but buying 600,000 H100 GPUs is more like a New Platform bet (Proven Math/New Capability).

You might argue ‘is the math really proven’? Well no, not yet. But even if Meta fails to build the perfect AI product, they will still own one of the most valuable compute clusters in the world. In an economy where compute is the "new oil," that infrastructure is a hard asset with intrinsic value. It has an asset floor… so the math is kind of underwritten if the balance sheet is strong enough to stomach the cash out.

Where Does Finance Play?

The role of the finance team changes drastically depending on which quadrant you are playing in. Think of it as a sliding scale of proximity to the controls.

On the Left (The Vending Machine): Finance is riding shotgun. You aren't driving the car - the Performance Marketer, Sales Leader, etc is - but you are in the front seat, right alongside them.

This is full-court press business partnering. You are the navigator checking the fuel levels (cash) and the speedometer (unit economics). If the LTV:CAC slips, you catch it immediately and tell the driver to ease off the gas. You are co-piloting the machine, dollar for dollar.

On the Right (The Moonshot): Finance moves to the back seat.

Our role here is not to judge the execution - it is to safeguard the perimeter. We determine the size of the bet ("You have $5m"), and we ensure it doesn't leak into the rest of the P&L.

Great CFOs know when to get out of the way. The temptation to demand an ROI forecast from an R&D team or a brand marketer is strong. If you force "False Math" onto a Moonshot, you will kill the innovation before it starts. Those calls belong to the product visionaries, not the finance boys… however strategic we might think we are.

How much you trust your creative teams to innovate well, is a key factor in a) whether you should have a moonshot capital pot and b) how much

Net Net

Allocating risk capital is a very different discipline to the operational rigor of MFCF generation. It is more cerebral, requiring you to channel the right decision-making systems to the right place in the business.

By grouping ‘like’ decisions together, you get a clearer system - one that focuses on the nature of the bet, not just where it sits in the P&L or balance sheet.

Next week, we will bring this all together into a governance system for cash management, from the boardroom down to the shop floor.

Keep your eyes peeled this week. I’ll be launching SimCFO, a new learning product for CFOs I’ve been working on for the last 18 months. It’s very f*cking cool.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: Ledge ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.