63% of controllers (you know who you are) still need to automate their AP processes

The problem? 99% of solutions overlook the AP adjacent processes that cause real friction. Think: supplier onboarding, invoice capture, approvals, payments, and reconciliation.

That's why Tipalti built a holistic solution for accounts payable that delivers best-in-class invoice and payment workflows alongside integrated fixes for all your other AP pain points.

One connected solution allows you to spend less time putting out fires and more time moving the business forward.

Learn how to remove manual processes from your workflow with Tipalti's free guide.

When FanDuel sold for $465m in 2018, you’d be forgiven for thinking the founders and employees cashed in…

After all, they still held about 40% of the equity.

But it wasn’t that simple. The company had raised $416m of venture funding to fight regulators and fuel growth. On the surface, a $465m exit looks like a 1.1x return on invested capital.

Far from a home run, but still, 40% of ~$50m isn’t nothing, right?

Well, in this case… it was. Those late rounds came with liquidation preferences. Investors were owed the first $559m of any exit. The math is brutal. That $465m is below the $559m preference stack, which means founders and employees were completely wiped out. On the bright side, they get to brag about the exit in their Twitter profile.

But, why didn’t they block the sale?

Because they couldn’t. In raising that capital, FanDuel’s board had been turned over to institutional investors, and the company had granted drag-along rights. If the 60% majority wanted to sell, everyone else got pulled along for the ride.

Powerless.

But the real kick in the teeth came later. Just two years on, the restructured FanDuel was valued at $4.2bn inside Flutter. Run the numbers on what that 40% common stake would have been worth, and it is enough to make you cry.

The lesson is sharp. One equity check is not the same as another. In the scramble to fund an astronomical burn rate, FanDuel went back to the well again and again. Each time, new investors demanded heavier prefs, more board seats, and stronger drag-along rights.

By the end, the 40% common stock still held by founders and employees wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.

Costly Capital

Welcome to part 4 of this 5-week August series, diving into capital structure design:

In week 1, we connected capital structure to strategy

In week 2, we defined the capital needs for your business

Last week, we broke down the different sources of debt

This week, we are going to get into equity and the role it plays in your capital structure design

The core characteristics of equity

We all understand that equity is where the uncapped upside sits vs. debt.

But as you saw with FanDuel, one class of equity does not equal another. So let’s start by defining the characteristics that define a class of equity:

Let’s take each in turn

1) Pricing (Valuation)

Valuation is the foundation for any equity transaction. It is the denominator in the dilution math. The key distinction to understand is between pre-money and post-money valuation:

Pre-money valuation is the value of the company before new capital is added

Post-money valuation is the value after the capital is added

For example, if the agreed pre-money valuation is $100 million and you're raising $25 million, the post-money valuation is $125 million. The investor's $25 million buys them 20% of the company ($25m ÷ $125m), not 25%.

Investors don’t “own” their own cash. They’re buying a percentage of the enlarged, post-money pie.

Valuation drives dilution, investor return models, and often control dynamics.

2) Sizing (Ownership & Dilution)

Sizing is the numerator in the dilution equation.

The size of the investment (and resulting dilution) can be driven by:

Capital need: How much money the company wants to raise

Dilution tolerance: The % ownership existing shareholders are willing to give up

Investor appetite: How much capital is realistically available from the market

The size of the raise directly determines the percentage sold, and therefore the dilution to existing shareholders. This cascades into:

Cap table dynamics: Headroom for later rounds, employee option pools, etc.

Investor rights: Protective provisions, board seats, or, at higher levels, effective blocking power

The dilution tolerance is critical as it will set the tone for the control provisions.

Here are some typical thresholds, and more importantly, what they mean for the parties involved (US-based):

A few notes on the above:

In the US, blocking rights usually come from protective provisions negotiated into the charter.

In UK/Commonwealth/EU jurisdictions, statutory rights kick in at specific thresholds. For example, in the UK:

>25% = can block special resolutions

>50% = controls ordinary resolutions

>75% = can pass special resolutions

Think of it this way: in the US, protective provisions are negotiated. But in many non-US jurisdictions, the law itself gives investors these powers.

3) Economic Rights

Economic rights determine how future cashflows due to shareholders get divided up. There is a potentially bottomless combination of options, but here are a few key ones:

Dividends: As a default, dividends will be shared pro rata between common stockholders. But each class of equity could be defined to have certain preferred dividend rights

Liquidation preferences: These exist to protect investors’ initial capital in the event of a sale or liquidation.

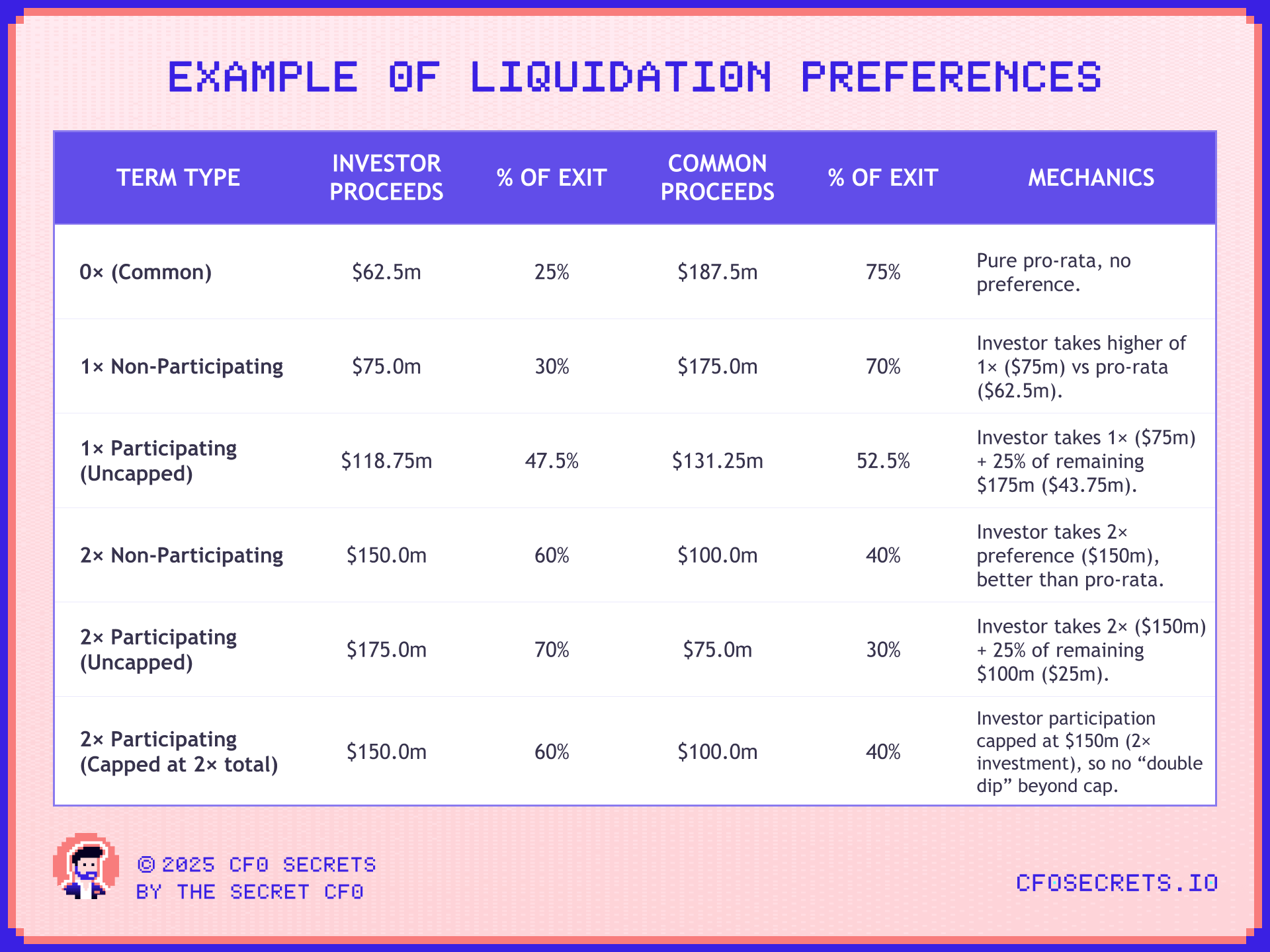

With liquidation preferences, there are three key parameters to understand:

a) The Preference Multiple

1x guarantees the investor gets their original investment back before common shareholders see anything

1.5x means they get their money back plus 50% more before anyone else is paid

2x means they get back twice their investment, and so on

b) Participating vs. Non-Participating

Non-Participating: Investor chooses the better of (a) their liquidation preference or (b) their pro-rata share of sale proceeds. Standard in most VC and growth equity deals.

Participating: Investor takes their liquidation preference first, and also shares pro rata in what’s left. This is a “double dip” and is more common in distressed, late-stage, or investor-friendly deals.

c) Caps

A cap can be added to limit participation (e.g., capped at 2x total return). This prevents investors from dominating upside outcomes while still protecting downside.

Let’s bring this to life. Imagine you raised $75m for 25% of your business. And then sold later for $250m. Here are five different scenarios, with radically different outcomes for management and investors:

Enough to make you go back and triple-check that term sheet, right?!

And it’s not just dividends and liquidation preferences that can affect the economic rights of stock. Anti-dilution protections for investors and conversion rights also play a crucial role in how the future share count (and therefore ownership stakes) will look

These mechanics matter. We saw conversion right math play out dramatically in our breakdown of the Peloton capital structure.

4) Control Rights

Control rights determine how much influence investors have over decision-making inside the company. The main tools are:

Board Seats: The right to appoint directors or observers

Directors get a formal vote and can shape the tone of board discussions

Observers don’t vote, but they still influence decisions just by being in the room

Protective Provisions: Veto rights over key decisions (fundraising, M&A, taking on debt, etc.). The problem here is that if you stack too many vetoes, you risk deadlock.

Voting Rights: Special voting thresholds on major decisions (e.g., M&A, IPO, new funding). These can be used as a middle ground. Example: instead of a board seat, minority investors might get a vote on specific high-impact issues.

5) Exit Rights

Exit rights define what happens when shareholders want or do not want to sell. A few key examples:

Drag-Along Rights: Allows majority shareholders to drag minority holders into a sale, forcing them to sell on the same terms. This is valuable because buyers usually want 100% ownership, not just a controlling stake.

Tag-Along Rights: The mirror image of drag-along. If a majority shareholder sells, minority holders have the right to tag along and sell their shares on the same terms. This prevents the minority owners from getting stuck with a new controlling owner they did not choose.

IPO Rights: The most common are lock-up agreements. Management and investors are restricted from selling shares for a period after listing (typically 180 days). The lock-up exists to prevent a flood of insider sales immediately after the IPO, which would crush the stock price.

Share Classes

It is rarely one term that makes or breaks a deal. More often, it is the combination of rights that matters. At FanDuel, it was not just liquidation preferences or board seats or tag-along rights in isolation, but the mix of all three.

Each unique bundle of terms creates a different class of shares (e.g., Class A, Class B, Class C, and so on). A small variation in one right is enough to justify a new class.

Some layering of share classes is inevitable once multiple rounds of institutional equity come in. But CFOs should avoid unnecessary proliferation. Keep the menu as short, clean, and consistent as possible. You don’t want it looking like a Cheesecake Factory menu.

Typical Classes of Shares

1) Common Stock

Terms mix: No preferences, no special rights. One share = one vote.

Where used: Founders, employees (via options/RSUs)

Pitfalls: Always last in the payout waterfall and highly vulnerable to dilution

2) Super-Voting Shares (Founder Control Stock)

Terms mix: Same economics as common, but with enhanced voting rights (e.g., 10 votes per share)

Where used: Founder-led companies, especially big tech IPOs

Pitfalls: Preserves founder control long after economic ownership shrinks, which is often criticized by institutional investors for poor governance. Can also create valuation discounts in public markets.

3) Preferred Stock (VC/Growth Equity Standard)

Terms mix: 1x non-participating liquidation preference, weighted average anti-dilution, board seat, protective provisions

Where used: Venture Series A, B, C rounds.

Pitfalls: Protective provisions can cause gridlock and aggressive anti-dilution punishes founders in down rounds

4) Participating Preferred (“Double Dip”)

Terms mix: Liquidation preference + pro-rata participation in the remainder

Where used: Late-stage or distressed deals when investors have leverage

Pitfalls: Investor economics dominate. A 25% investor can end up taking 50–70%+ of exit value

5) Convertible Notes/SAFEs (Simple Agreements for Future Equity)

Terms mix: Convertible into equity at next round, usually with discount and/or valuation cap. Few governance rights.

Where used: Seed stage, early rounds where speed matters more than structure

Pitfalls: Stacking too many can blow up the cap table, and low valuation caps create hidden dilution bombs

6) Redeemable/Preferred with PIK Dividends (Structured Equity)

Terms mix: Preferred shares with mandatory redemption rights and/or accumulating PIK dividends

Where used: Private equity, distressed financings, mezzanine-style deals

Pitfalls: Functions like debt and compounding obligations can force a sale or drain liquidity

VC Backed Cap Tables

Startup and VC-backed companies often end up with the most complicated equity structures. You could see all six of the above archetypes in play, with subclasses based on different terms such as liquidation preferences and voting rights.

Zuckerberg’s super-voting shares (10:1) have allowed him to maintain majority control of Meta’s board since inception (twenty years if you want to feel old), despite owning less than 15 percent of the economic interest. It’s a good reminder that economics and governance are two separate dimensions.

The potential complexity here is a minefield. Often, it only gets simplified at IPO.

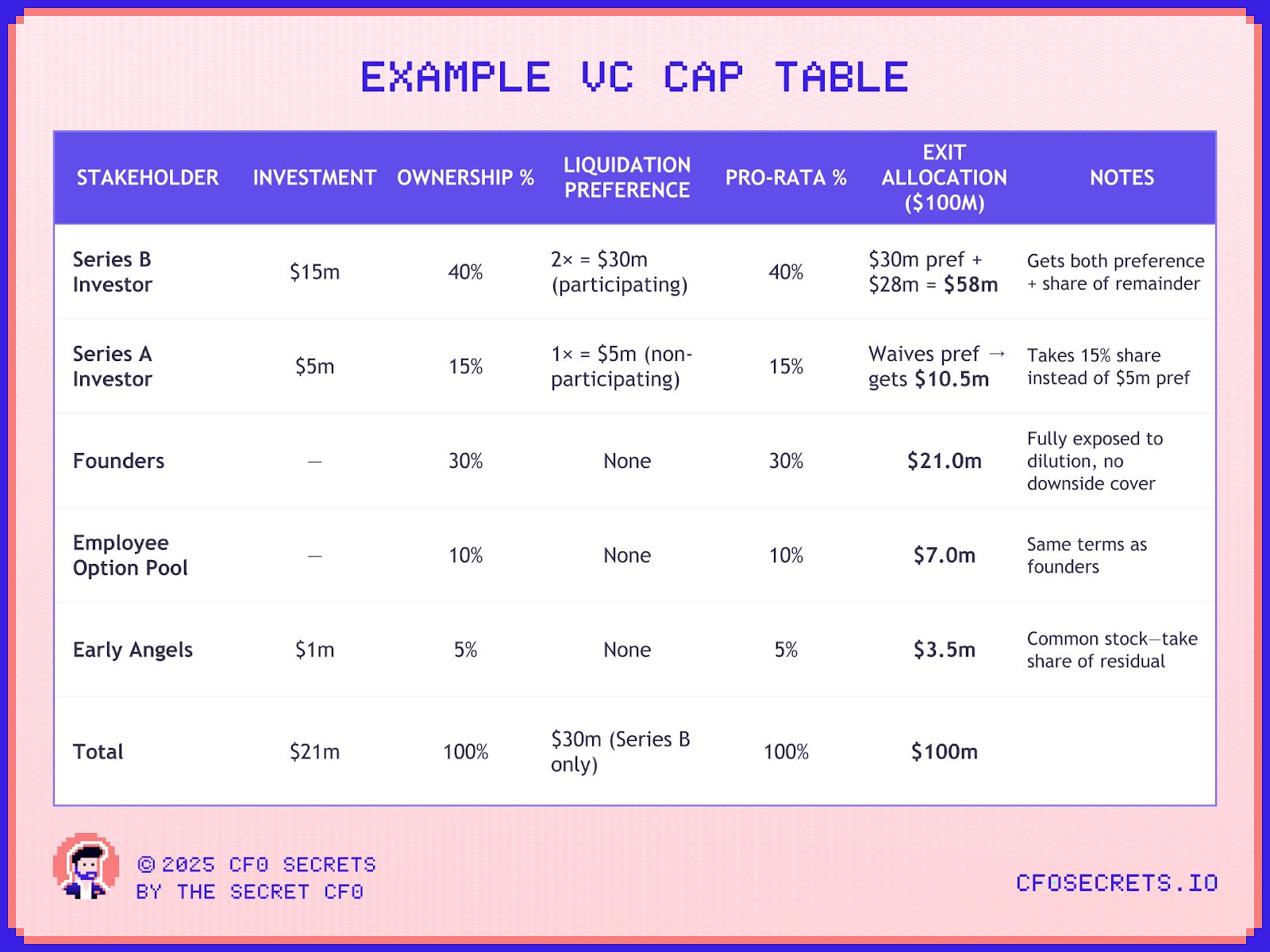

Here is an example of how a cap table could look after Series B. With an example of the payout waterfall based on a $100m exit:

PE Backed Cap Tables

PE-backed equity structures are often simpler. There are typically two classes:

Investor Class: Preferred stock with a 1–2x liquidation preference, often carrying a coupon or accruing dividend to hit the fund’s cost of capital hurdle (for example, 8 percent). With full drag-along rights and total control of board seats, the PE fund not only gets its capital back first, but also compounds its return annually before management gets a dip.

Management Class: This is common stock. Management’s stake is a pro-rata share of what is left after the PE fund has been paid its investment back, plus the compounding preference dividend.

The PE structure is management-onerous (by comparison), but simpler to understand and easier to model. It also is reflective of the ‘gun for hire’ type manager a PE fund is looking to execute their plan. Here is an example based on a $180m exit after a 5-year hold on a $61m purchase price (with management contributing $1m):

This example focuses only on the equity. But in a typical PE deal, the debt stack is just as important, and often more aggressive.

Public Cap Tables

Public companies are the simplest (in terms of equity classes) on paper. The vast majority of shareholders hold the same class of common stock. Everyone ranks equally in the payout waterfall and has one vote per share.

The main variations in public markets are:

Dual-class structures: As with Meta, Alphabet, or Snap, where insiders hold super-voting stock

Preferred stock: Rare but possible in certain financial or distressed situations

Debt and convertibles: While not equity, these instruments can blur the picture for total shareholder returns

For most public companies, simplicity of capital structure is by design. Investors and regulators demand transparency.

Private / Family Cap Tables

There is no such thing as a “typical” structure. The default is usually simple common stock, but over time, many of the same features seen in institutional equity can be written into family or private agreements.

In multi-generational family businesses, it is common for economic rights (dividends, profit share) to be passed down faster than control rights (voting, board seats).

The Role in the Capital Structure

Ultimately, what new equity is available to the CFO will depend upon:

Risk profile: Higher risk drives investors to demand stronger protections, lower risk allows simpler equity

Capital vs deal scarcity: If capital is scarce, you take investor terms, if deals are scarce, you dictate terms

Quality of the story: A clear, credible plan shifts investors from protecting downside to chasing upside

Management reputation: Proven teams get trust and lighter terms, unproven teams face heavy controls

Stage of the business: Early stage means light instruments, later stage often means layered and investor-skewed equity

Negotiating leverage: The final terms reflect who needs whom more at the table

The most powerful dynamic here is the “swim with the tide” effect. When capital is rushing into a sector, terms get looser, structures get cleaner, and valuations run hotter.

We are seeing this in real time with AI. Investors are competing for exposure, which means companies have the luxury of raising on simpler, founder-friendly terms. The opposite is true in cold sectors.

And much like we said in week one, the more you can operate within established funding ecosystems, the easier it is to access equity capital.

It is the tension between equity availability, debt availability, and the company’s capital needs that ultimately drives how you put the capital structure together:

Net Net

Equity is not just “ownership,” it’s a contract with real consequences.

It dictates who gets paid, who makes decisions, and who controls the outcome when things go right… or wrong.

As FanDuel’s story showed, even holding 40% can mean zero economic return if the structure is stacked against you. The goal is to make sure you raise the right kind of equity, at the right time, on terms you fully understand.

Next week, we’ll take a real-world scenario and walk through the decisions required to build a capital structure: what mix of debt vs equity, how to prioritize flexibility vs cost, and where the control should sit.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

Find amazing accounting talent in places like the Philippines and Latin America in partnership with OnlyExperts (20% off for CFO Secrets readers)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: TIPALTI ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.