Manual AP isn’t just tedious, it’s risky

It leads to errors, late payments & compliance gaps.

Most finance teams are still stuck with paper, spreadsheets, or half-automated tools that only cover part of the process. The real friction lives in vendor onboarding, invoice matching, chasing approvals, and reconciling payments.

That’s where Tipalti comes in.

Tipalti closes every gap with one connected AP solution. No silos. No band-aid fixes. Just smoother workflows and more room to scale.

It’s about to get real

Frostbite was no rocket ship, but it did manage to reach orbit (which is more than most brands in the space can say)...

The specialist winter DTC brand had grown to $200 million in revenue and a 10% EBITDA margin on about $40 million of outside funding. Not a unicorn, but solid, and with momentum.

It wasn’t quite the phenomenon that Canada Goose was, but its jackets are also Everest-rated… and it definitely had its own unfair advantage.

Part of the magic was a negative cash conversion cycle. Customers paid up front, suppliers got paid later, and Frostbite scaled on other people’s money. Until now.

As volumes climbed, their biggest supplier demanded faster payment. That one shift cracked open the funding model and exposed how fragile it really was. It was like being caught on Mt. Washington in a Speedo instead of a Frostbite Col-Tec Thermo Layer jacket (in navy).

Seasonality made it sharper. Cash drained every summer as inventory built, then surged back in Q4. The whole business leaned on a bank revolver. One performance blip and the bank could take it away.

Suddenly, the questions changed. Should they just absorb the working-capital hit and find a way to fund it? Or take control of their destiny and build a factory, a $100 million capex commitment that could lift gross margins and accelerate growth? And how much stress could the revolver really bear?

Those would be the questions keeping management up at night.

Well… they would be, if Frostbite were real. It isn’t. But it IS our fictional case study for this week’s post.

Welcome to the fifth and final part of this series on capital structure design.

So now we’ve got the ingredients. It’s time to bake the cake.

But what does “fit” actually mean when we talk about a fit-for-purpose capital structure?

At its core, a well-designed capital structure must deliver:

Strategic alignment

Flexibility

Liquidity

Cost efficiency

The right investor fit

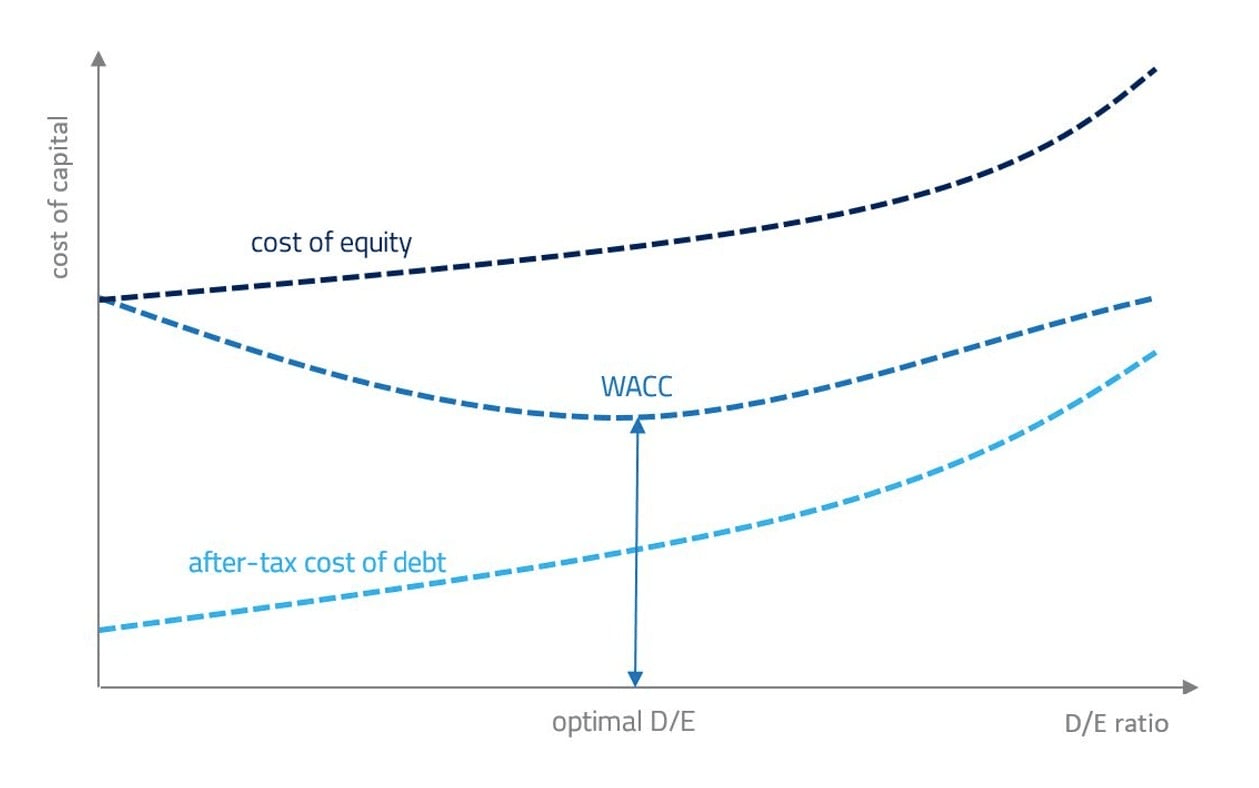

Most finance theory reduces capital structuring to a cost optimization exercise: balancing the cost of debt and equity to find the theoretical minimum WACC. You've seen the curves…

That’s a luxury reserved for mega-cap CFOs with investment-grade balance sheets or PE sponsors engineering capital in their portfolio like gods of commerce.

For everyone else, the spreadsheet doesn’t throw out the answer.

Capital comes in many flavors. Debt isn’t one line on a chart, and neither is equity. What’s optimal in theory may be unachievable, or come with strings that are strategically unacceptable.

Which is why this is a qualitative exercise as much as a quantitative one.

There is no universal answer or framework to be answered. But there are first principles we can apply. And to bring those to life, we’ll use a worked example.

A Worked Example: Frostbite

You’re going to want to bundle up for this one.

Back to Frostbite, our example company. For context, here’s a P&L summary (2025 latest forecast + 2024 actuals):

How is it funded?

There are three legs to the capital structure.

First, equity. Frostbite has raised $41 million across three rounds, mainly to fuel the early marketing engine and the expensive customer acquisition push. These days, the P&L covers growth spend out of operating cash flow. The cap table now looks like this:

Second, working capital. Frostbite has long enjoyed a negative cash conversion cycle of ~20 days, meaning growth has been ‘self-funding.’

Third, debt. The company leans on a revolving credit facility (RCF) to smooth out seasonality. About 70% of sales land in Q4 and Q1, which means a big inventory build in Q3 before cash floods back in during winter. The revolver, secured against the business, is sized at $30 million and is typically 80% drawn at peak.

Frostbites Strategic Challenges

The long-range planning process has surfaced a set of, well… chilly… issues that directly shape Frostbite’s capital structure:

Working capital is turning from friend to foe. The company’s negative cash conversion cycle was propped up by a manufacturing partner on 90-day terms. That partner has now signaled that the party is over. The terms will move to 45 days. The result: a ~$30 million working capital unwind over the next two years.

The revolver is nearly maxed out. Frostbite’s $30 million facility is already 80% drawn at the seasonal peak. Growth in sales only makes the seasonal swing larger, and the current line isn’t big enough to absorb it. More growth equals more volatility, and the current revolver can’t stretch much further.

Growth comes with trade-offs. There is natural demand growth of ~10% annually, but management sees potential to grow up to 30% per year. Doing so would require a big brand marketing push. In the short run, marketing efficiency would collapse, EBITDA margins would compress to zero, and the funding gap would widen. Longer term, the additional scale would accelerate margins and profitability, but only if the near-term cash burn can be financed.

Manufacturing is the elephant in the room. Frostbite is fully dependent on third parties. That constrains product innovation and leaves a supplier margin on the table. At the current scale, Frostbite could build its own plant. Bringing manufacturing in-house would transform gross margins, but it comes with a CapEx bill of ~$100 million.

This is a long way of saying… the current capital structure has run its course. Time for something new.

Frostbite’s Unfunded Model

As part of Frostbite’s long-range planning (LRP) process, they produced three different scenarios of an unfunded model. (For more on ‘unfunded models’, read week 2).

Firstly, a base scenario that shows profitable but modest growth. It comes with the short-term challenge of a working capital unwind to manage alongside the change in supplier terms.

Second, a growth scenario, which shows the costly up-front marketing investment, but the exciting payback towards the end of the plan:

Finally, a scenario that overlays the manufacturing investment on top of the base plan:

Capital Requirements Profile

So, how do we turn this into a layered capital requirements profile (again, check out week 2)?

It could look something like this:

The revolver exists to fund seasonality, which is expected to grow over time. The base plan will produce cash flow from Dec-28 onwards, but we will also need to build some downside/sensitivity in to make sure our capital structure is resilient if demands soften, margins fall off, or customer acquisition costs increase.

Then we get to the options:

Funding for the more aggressive growth plan peaks at $59m in 2028 (but actually pays that back and more by 2030)

Capex plan will need $88m, peaking in 2028

So, you see the problem here.

Some exciting strategic ideas. In fact, if Frostbite can land the growth and the manufacturing plan, they could have a business with EBITDA of ~$200m by 2030, a 10x increase on today.

But to get there, there is a crunch of cash required, peaking in 3 years. Not helped by short-term working capital challenges.

The question becomes, what funding is available, and how would you structure it to manage the risks and capitalize on the upside?

Let’s start by seeing what debt we might be able to get for the business:

Debt Capacity

Frostbite figure out their theoretical debt capacity for each scenario on the following assumptions:

Interest cost of 8%

Debt cap of 80% of assets

Leverage cap of 3.5x EBITDA

Minimum interest coverage of 5x

I’m going to skip the detailed workings, as we covered this in week 3:

Debt capacity is constrained in the base scenario as the business is asset-lite

In the growth scenario, as EBITDA is growing faster, it opens more ‘cash flow’ based borrowing capacity in the later years. But the constraints on EBITDA in the short term cause a problem.

In the factory build scenario, debt capacity grows as the capex investment builds hard assets that Frostbite can leverage

Note, we also model for the two scenarios layered on top of each other, which shows a combination of both the short-term constraint caused by the growth plan, and longer-term growth in asset values

Let’s overlay the combined scenario theoretical debt capacity with the capital requirements profile, and suddenly, the capital structure design conundrum for this business becomes clear:

By 2029, this business will be able to fund the business on conventional debt it needs. Even on the most aggressive scenario. But to fund the plan to get there, it’s going to need equity or less conventional/expensive debt.

Equity Capacity

Equity availability to cover the gaps in years 1-3 shouldn’t be a problem. This is a growing brand that has established VC funding in the cap table. The question is at what cost?

The last round was raised at a particularly hot point in the cycle, at a generous valuation. A new raise is likely to be raised at a lower valuation (a down round). And, if nothing else, the perception that comes with that will create risk of new investors insisting on punitive terms: more board seats (management has a board majority of 3 vs 2 currently) or more aggressive liquidation preferences. We saw last week how that ended for FanDuel.

What Options Are On The Table?

Having done the theoretical work, the Frostbite CFO gets out and speaks to banks, VC funds, and even alternative funders to understand what the options and terms would look like to fund their cap structure.

Let’s start with the working capital requirement:

Good news on the revolver: Frostbite’s existing commercial bank group has agreed to renew the RCF and increase the limit to 2x 2025 EBITDA, providing $40M total capacity. That’s an additional $10M of headroom versus the current draw.

Thanks to a strong relationship and consistent performance, the lenders have agreed to structure this as a cash flow-based facility, despite the lack of traditional AR or inventory coverage.

Critically, the bank has also indicated support for an accordion feature, which would allow Frostbite to expand the facility by up to $20M in the future, subject to hitting defined EBITDA thresholds. This provides a clear path to scale the revolver in line with business growth.

Alternative working capital solutions, such as trade credit insurance or supply chain finance, remain on the table but come with higher costs and execution risks. These are best treated as contingency options rather than core components of the plan.

Next up, let's see the options for funding the capex project:

The factory decision is a big swing. It’s something Frostbite management sees as critical to their strategy, but fundability is the issue. $100M of capex with clear upside on gross margins and supply chain control, but serious funding implications.

With a ‘hard asset’ to secure funding against, they prioritize bank options. They can get a mortgage-style term loan for 60% of the build cost, but that still leaves ~$40m of the build cost without a plan.

And there is no volume dial on this one, it’s $100m or nothing. There are options to top up with some equipment-specific funding options, but in practice, there will likely need to be some equity or mezzanine funding.

Which takes us onto funding the growth plan:

The growth plan is ambitious, scaling from $200M to $685M in revenue by 2030. In the base case, the top line doesn’t even reach $300m. The difference is worth over $80M in additional EBITDA. There’s real value to be created, but it requires serious upfront capital to unlock it. The upfront marketing expense needed to get sales moving is real risk capital.

A Series C round at a $200M post-money valuation could raise $40M to $80M, but would dilute the founders and management into a minority position. So, control provisions will be vital.

Convertible or mezzanine debt avoids dilution at entry and gives the plan space to perform. But the conversion mechanics have to be tightly negotiated. If the growth doesn’t come through, and the convert kicks in low, it can be just as dilutive, just delayed.

Merchant cash advance is a creative solution. It’s not big enough to write the whole ticket, but it could be used tactically. These are short-term, high-cost debt products, repaid daily out of revenue. They’re not designed to fund strategy, but they can bridge timing gaps, like front-loaded CAC or a seasonal inventory spike.

The nice thing with the growth plan is unlike the capex plan it’s not ‘all-or-nothing’ it can be dialled up or down to fit the capital options.

Options for the Capital Structure

So, let’s step back. Where does this leave Frostbite management? When you unzip the Frostbite ICE-Tec Sherpa Lined Outerwear, here are its real options:

Option 1 - Keep it boring

There is a safe but unspectacular play … keep doing what they are doing. Raise a new, more flexible revolver, and keep growing modestly. If we build that into a funded model, the cashflow would look something like this:

There is still an opportunity to double EBITDA over the next five years, with no further dilution and good downside protection. The conservative option.

Option 2 - Debt Maximize

If Frostbite wanted to maximize the amount of new capital but minimize dilution, the play would be to build the factory. On top of the RCF, they could get a $60m mortgage, and take some additional tactical debt like the Merchant Cash Advance for maybe another $20m total. This leaves them $20m short of the capital needed to build the factory.

That gap could be plugged by equity, assuming a further 10% dilution (valuation of $200m). Or a convertible note. The benefit of this approach is that it unlocks the huge gross margin improvement through insourcing, which by year 3 is yielding cashflow that could be invested into a delayed version of the growth plan. (Taking advantage of the ‘volume dial’ available in the growth plan.

Cashflows could look like this:

More than 3x the EBITDA of the base case for just 10% dilution. Seems smart. As long as the debt isn’t too restrictive.

Option 3 - Focus on growth

Vertical integration comes with risk. Manufacturing is a new competence for Frostbite. And the debt will reduce flexibility. Maybe Frostbite should stick to what they are good at and just grow hard. That will mean funding up front marketing costs, which will mean a new equity round. $60m should do it, but it unlocks an attractive terminal EBITDA.

Option 4 - Go Big

Finally, Frostbite could bet the farm. Raise the money they need now to build the new factory and grow as hard as possible. That will mean raising $60m in equity and maxing out the debt capacity. It puts risk and more equity dilution into the business, but it would expect to reach $200m in EBITDA by year 5:

Picking a Direction

The correct direction will come down to many things, but mostly the business’s risk appetite and the founders' appetite for control/dilution. Let’s assume the founders are targeting a full exit via sale in 2030, and are optimizing for that outcome.

Let’s weigh the options against each other, assuming two possible outcomes in 2030: one a sale at 8x EBITDA and another “downside scenario” at 6x a sensitized EBITDA:

With this context, the choice seems more clear-cut. Option 2, the debt-maximizing option, blends the ambition of the growth plan (albeit delayed) but uses the improved margins from the capex investment to fund that growth.

And by reducing equity dilution, it achieves an upside for the founders and employees on par with the ‘go big’ option at ~$400m. But also presents a better downside scenario in the event things don’t go to plan (in option 4, the liquidation preferences take a bigger bite of the smaller proceeds).

So option 2 dominates options 3 and 4 as a capital structure and strategy in this case.

For a highly conservative management team, option 1 might still be more appealing, purely because it has the lowest ‘go-to-zero’ risk.

Wrapping up Frostbite

In practice, we would model all of these options out into fully funded 3 statement models under different sensitivities. This will help test the outcome and ensure the circularity of the interest and cashflow modeling feeds in correctly. Tax shield and Net Operating Losses (NOLs) play a big role too.

But I simplified those assumptions for this scenario, so we could focus on the key lessons of this series; the interaction between the capital structure and management strategy.

Net Net

And that brings us to the end of this series on capital structure design. Your job as CFO is about so much more than delivering the lowest cost capital structure. It’s about delivering the optimal structure to fit the business. Sometimes that means the cheapest. But not always.

There are topics here we will expand on in the future and break out into entire series, so we can go even deeper. If there is something specific you’d like to see, please hit reply and let me know.

If you’re looking to sponsor CFO Secrets Newsletter fill out this form and we’ll be in touch.

Find amazing accounting talent in places like the Philippines and Latin America in partnership with OnlyExperts (20% off for CFO Secrets readers)

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:: Thank you to our sponsor ::

:: TIPALTI ::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

What did you think of this week’s edition?

If you enjoyed today’s content, don’t forget to subscribe.

Disclaimer: I am not your accountant, tax advisor, lawyer, CFO, director, or friend. Well, maybe I’m your friend, but I am not any of those other things. Everything I publish represents my opinions only, not advice. Running the finances for a company is serious business, and you should take the proper advice you need.